A CHRISTMAS STORY.

This is a new Christmas story, written by regular contributor Lorna Campbell. It is well written, centred in Scotland, and involves Wallace, Bruce, Andrew De Moray and Bannockburn. I thought many of my readers would enjoy the story. When Lorna sent it to me it was very well illustrated but sadly my WordPress programme doesContinue reading "A CHRISTMAS STORY."

This is a new Christmas story, written by regular contributor Lorna Campbell. It is well written, centred in Scotland, and involves Wallace, Bruce, Andrew De Moray and Bannockburn. I thought many of my readers would enjoy the story. When Lorna sent it to me it was very well illustrated but sadly my WordPress programme does not allow me to reproduce it with the illustrations.

A traditional Christmas story

flesh of my flesh, bone of my bone nno Domini 1314: Advent long begun, and the depleted villagers looking forward to Christ’s Mass. The revelry, a little muted this year, would take place after the celebration of the Holy Day in their little church, built years ago by the young lord’s grandfather, when Father Blaine, his predecessor had been a young priest, and after the blessing from Father Gartnait, as kindly a Christian soul as ever walked the Earth. He tended his poor congregation, so scarce of men now, as if each were a gift from Heaven itself and just for him, and he worried incessantly over their tribulations and trials, petty and serious alike, as if they were his own children, sprung from his own loins, and, if he could not always supplement their meagre sustenance with berries and apples from his little orchard plot, or a hearty soup with vegetables from his tiny, but fertile, garden patch, he could feed their souls with his prayers.

A wisp of wood smoke from a hearth fire floated above him and curled lazily around his head. For a heart-stopping moment, fearful memory dragged him back to his first-ever visit to the town, a boy of barely twelve summers, into that baying, jeering crowd, jostled and pushed aside by people he barely recognised as human, faces twisted and slack with avid glee at the sight of an elderly creature in stinking rags, eyes popping out, wild with horrible anticipation of what was to come, as that

same smell permeated the air. He remembered her toenails – or, rather, the pulpy raw flesh – and the remembered sight still pulled him, sweating and muttering, from his nightmare. Father Blaine had grabbed him by his collar and hurried him away. He had recognised in the boy a sensitivity not yet bred out of him by unremitting toil and a rude existence around the pigsty, had done his best to save him from his smothering fate by taking him under his wing and educating him for the Church. This day, a boorish, bitter one, the clouds full to bursting with the promise of snow, he was worrying about one of his parishioners in particular: her name, Marsali, big with child, to be brought to bed any day now, and her man deemed lost in the last battle. All women must suffer the pangs of childbirth, he knew, and the pleasures of new love were all too fleeting. Her life, as all the widows’ lives, would be harder for lack of a man to cut the wood and peat, to till the soil, and to keep her warm in the cold of a winter’s night.

Father Gartnait might be celibate, but he was no innocent in the ways of the world. He could not help but wonder if she would bring forth her child on the Holy Day, bequeathing great good luck on such a child, and he was ready to baptise the tiny creature immediately, in recognition of its frailty and tenuous hold on life, as all such children born to the poor must be but a step away from death’s grip even as they drew their first breath. Father Gartnait, like his mentor, Father Blaine before him, was a man born out of his time, although he could not know it, a man who overlaid superstition with reason and compassion.

Buain, the hairst, had been good enough this year as if the fields themselves recognised that all of Alba Scotland, had been granted the Lord’s mercy six months ago when everything could have gone so badly for the outlaw king and his benighted realm, ground down under the heel of the Sasunnach lords for so long. Those who delved and tilled and herded the beasts knew well the sharp claws of hunger. War, famine, drought, pestilence must be endured by those who had little but their prayers to sustain them, and there were times when Father Gartnait despaired of those prayers being answered.

1

The women, children and old men had worked hard and long to ensure that they would not starve, and he had been honoured to work alongside them, full of hope, even though his back ached so much he could barely straighten it and had had to rub a herbal lineament into the strained muscles each evening, to soothe them.

His hands, wielding sickle and spade, had been covered in blisters that he had been obliged to treat with a moss poultice. He had reddened in shame at his own weakness: lordlings and churchmen alike with their soft flesh, made poor work of hewing and delving. Even so, he had rationalised, those who hew and delve are not often called upon to read Latin and Greek. A kind of balance existed in the world, yet little fairness.

He remembered the old lord, Andrew de Moray, long in his grave, sending out the call – before the turn of the century, it had been – and the men, the young ones little more than boys, and their fathers, too, answering the call and leaving the village and their womenfolk, and the old men and the children, to fight beside their lord and the Wallace. There had been no choice for them as he was their liege lord and they his tenants, and, in any case, they knew what to expect if the Sasunnach king, Edward, marched north. All they had was their strips of land and they would fight to keep them – to die, if the good Lord willed it, and die they had done, some of them, from this village and from many another from the lands of Moray and from other parts of Scotland, from the isles to the glens and from the fisher villages to the border.

He had counted 30 men and boys out, and 25 had returned, and most of those with a wound, one or two with deep, suppurating gouges and slashes that refused to heal, so that their lives, seemingly spared, had been no more than a long, drawn-out painful death that mocked their return to hearth and family. Their lord had returned to his lands in Moray, broken and dying, and it was said that his lady widow, like Marsali now, full of child, had been distraught in her deep mourning. It is the truth, he thought, that the poor and the wealthy both return to the clay from which they sprang, their widows mourn alike, and their end is the same, though the one be returned to the earth in a poor winding sheet and the other in a fine, silk-lined coffin. In that, there was a certain justice, he mused, for the injustices of their different life stations and paths. Am I becoming a heretic, he asked himself, alarmed at his own audacity in matters of Scripture? Did the Good Bible not say that all men must cleave to their station as the beasts of the field to theirs?

Marsali had waved her young husband, Alexander, off to a new battle, just as her mother, Jonet, had waved off her father who had not returned with Andrew de Moray, but was, according to a village man who had witnessed his burial, been thrown, with hundreds of others, into a grave pit. Father Gartnait had said prayers for all those who had not returned and for those who had, and he had beseeched the Good Lord to take all of the dead to His bosom in Heaven though their bones might lie in a distant field of battle. He had prayed, too, for the little son of de Moray, barely five summers, and also Andrew by name, who had been snatched from his mother’s skirts by the English king, as hostage for the good behaviour of his kinsmen and their tenants and peasants, and carried off to England.

The late King Edward I, it was said, or so Father Gartnait had been told, in Elgin, by visiting monks, had engraved his chosen insult on his tombstone in Westminster Abbey: Hic est Edwardus Scottorum Malleus (Here lies Edward, Hammer of the Scots). Pah, Father Gartnait thought, dismissing the Sasunnach’s arrogance: he remembered how the old war-monger had marched north with his host and lain waste the lands of those who stood against him, yet, the English king was, in truth, an enigma and it was whispered that the boy’s long sojourn in England had not been arduous and had not dented his allegiance to Scotland and her own king, be it that the Bruce had spent many years as a wolf’s head with a fortune on his scalp.

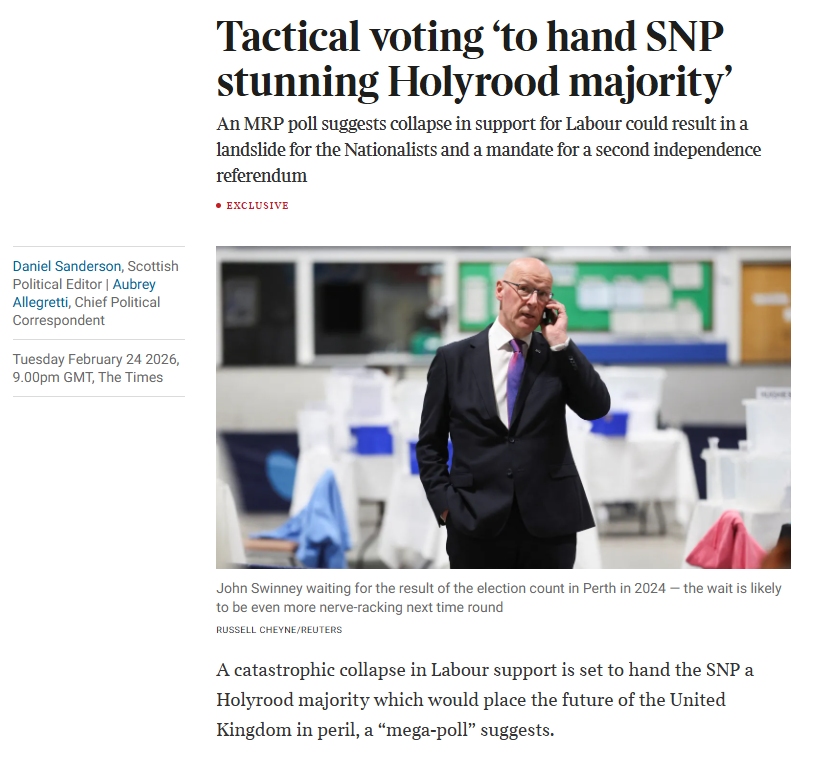

In the young lord’s name, the lands of Moray rose again when the Bruce sent out his runners to every parish, and the great Earl of Moray, Thomas Randolph, commanded a schiltron, comprising men from his own lands in the south of Scotland and those from the lands of the young Andrew Moray. The great Cathedral of Elgin, established in 1224 when the Seat had been moved from Spynie to Elgin by the then Bishop of Moray, yet another Andrew Moray, rebuilt and extended in 1270 after the fire which had consumed a large part of it, had been lit up with hundreds of beeswax candles after the two-day battle of Bannockburn and the rout of the Sasunnach army under the old king’s son, also Edward a fool for his favourites, it was whispered. The magnificent building was indeed ‘The Lantern of the North’ that day, in the fullest sense, a place of learning and light, and its great bells pealed out across the Laich and beyond, so that every village for miles around heard them and knew that Alba Scotland had been saved from sword and fire.

The women had waited with a mixture of pride and anxiety for the return of their menfolk, every heart full of fear that it might her man or her son or her father who would not come home. Most of the men did return, in twos and threes, over a long period, some supporting an injured comrade, and, as each little group entered the village, the keening of the women who had lost their mate or son or father would begin again and freeze the hearts of those who waited still. After three months, the last of the stragglers had returned, some with a story of the death of a village man, others with eyes that looked out but saw nothing but blood and gore and severed limbs and heads, and would never again see else. The only man that no one was sure had been slaughtered or wounded was Marsali’s Alexander, each returning survivor shaking his head: “I did not see him fall.”

Marsali never seemed to lose hope: she had been a child of limitless faith; and now, a young woman whose faith led her to pray fervently to the Christus Mater; and, in his heart, the priest envied her, her implacable certainty. “He will come back to me and his bairn,” she told Father Gartnait who had not the strength to dampen her hopes, but who, in his own heart, feared that the young man lay in one of the grave pits on that far-off Stirling battlefield. He kept lighted a tallow candle to illuminate Alexander’s way home; it was all he could do for the young woman, beyond his prayers for them both and for their unborn child. Every day, Marsali came to his tiny stone church, stooped through its arched entrance door, and prayed beside the candle for the return of her young husband, Alexander, to the village and to his family, soon to be augmented by the child in his wife’s belly. Each day passed very like the last, with no sight of the young man and no word running ahead of him. Now, Christ’s Mass was a day away, snow was beginning to fall thickly from a sky that was the very colour of the lead on the Cathedral roof in Elgin, and the cawing rooks, like a flock of noisy Benedictines, retreated to their woody tower cells, to squabble noisily and preen their ragged, tattered feather habits, huddling together in bickering groups to keep the dense cold at bay.

Father Gartnait peered out, through the spattering sleet, his little, reed-thatched cottage adjoining the church, and wondered whether Marsali would appear today. It was now six months since the battle they were calling the Bannockburn away in that far-off place they called Stirling, where it was said that a huge castle dominated the countryside and whoever held it, held Scotland. The village and the rest of the Moray lands were returning to a kind of resigned normality, and the young lord, Sir Andrew Moray, had returned from his enforced sojourn in England as a hostage of the Sasunnach king, no longer a small boy, but a youth of almost seventeen summers.

The boy had proved to be a good lord thus far, sending runners to all his towns, villages and hamlets with gifts of venison and game birds, grain and winter greens for his tenants in gratitude to the Good Lord and his faithful people for the deliverance of Alba Scotland, her king, and his own life. It promised to be a better season than many before, and even those who had lost menfolk were rallying a little now, accepting grudgingly as peasants did, their lot in this life, hoping for salvation in the next. What could not be changed must be endured, thought Father Gartnait, not at all sure that it should be so. At least they would not starve this winter, thanks to the young lordling and his largesse augmenting the fruits of their own labour.

Marsali appeared, suddenly, as a shrouded figure out of the swirling whiteness and hurried into the church. He recognised her somewhat faded, but warm and fine, blue and white and green woollen cloak, a hand-me-down gift on her marriage day, from the young lord’s mother; it had always reminded him of the splendid stained glass windows of the great Cathedral, which were said to be of a splendour seldom seen in northern Scotland. Father Gartnait hurried after her, resigned to her – and thus his – daily vigil. “It has been a very long time now, Marsali,” he suggested hesitantly because that kind man would have rather bitten his own tongue out and spat it into the sleety snow than caused the young woman greater distress. “You must think of the child, Marsali. Your mother will help you when your time comes?”

The girl nodded, but absently, lost in her own thoughts. “He will come, Father. I know he will come very soon. The Lady will answer my prayer.” She gazed at the face of the Mother of Jesus. Father Gartnait sighed and began the prayer, the little candle guttering and flickering in the cold currents of air that were pressing freezing fingers into every corner of the little church, seeking out tiny cracks in the masonry through which to pass them and touch, with icy precision, the uncovered parts of the body. His neck and spine felt their cold caress.

3

He shivered in his woollen robe and, weak flesh that he was, he longed for his little fire next door and a cup of hot posset to warm his belly, not to mention his indulgent, honeyed oaten bread, which, if he was not careful, would pave his own road to Perdition. As if reading his uncharitable thoughts, Marsali rose off her knees with difficulty and steadied herself. “I must go, Father. Alexander will be coming. The Lady will answer my prayer.”

The priest wondered if the young woman had lost her wits to grief, but she did not appear to be any less lucid than usual, and was actually quite cheerful. All the same, he could not help but worry, and he had to prepare for the Christ’s Eve Mass when all the villagers would come to pray and offer thanks for the birth of the Lord Jesus of Nazareth. This time of year invariably filled him with such love for his fellow creatures that it could always bring a tear to his eye. As he was leaving, he glanced at the little, rudely carved nativity, at the misshapen, tiny Jesus wrapped in swaddling rags, a gift from a grateful parishioner with more goodness of heart than skill at carpentry, and, again, he prayed silently that Marsali would deliver her child safely.

He knew that the little cemetery beyond the church walls was testament to the dangers of childbirth. Women, from Eve, and down through the ages, had their own travails to bear just as the menfolk had, and, because he was such a naturally kind-hearted man, he could not, as so many in the Church did, blame the womenfolk for theirs. The good Lord had created man and he had created woman, and, as far as he could see, womenfolk were no worse than menfolk. Sometimes better. Was Eve not the source of humanity’s fall from grace? He never could read Genesis without considering that Adam might have been just a little complicit. Another heresy? Dear, dear. That cheery fire with its leaping, warming tongues of orange and red, and his hot posset beckoned seductively, his frozen fingers and toes, his creaking bones and his empty belly answering avidly, drawing him back to his hearth. Marsali’s mother appeared at Christ’s Eve Mass, as his sharp eyes picked out each of his parishioners, but there was no sign of Marsali, and he could scarcely concentrate on the service, so distracted was he with worry. The young woman was a devotee, her belief deep and constant: she had been so from the day she could toddle to church; and, truth to tell, he believed in the early days that she might leave the village and join the nunnery in Elgin, and he would have encouraged her to flee the travails that all women rooted in the world must endure. However, Alexander had taken her fancy and Father Gartnait had to admit, with a chuckle, that Marsali was too rooted in the world to be a nun. That life would have broken one of her nature. It is also God’s will that man and woman should come together and produce children, he thought then, and did not Our Lord say: “Suffer the little children to come unto me”?

The moment the Christ’s Eve Mass was over, he sought out Marsali’s mother. “Where is Marsali?” he asked. The poor woman looked frightened. In truth, she had not seen her daughter since before the service, being tardy herself with so many domestic tasks to complete, and was very worried because Marsali would never miss Christ’s Eve Mass unless something was very amiss. She feared, she said, that her daughter was in childbed and all alone in her travail. She would go to Marsali’s little cottage and find out. Her daughter could be in labour, trying to bring forth the child with no woman present to help her. Father Gartnait urged her to wait for him, and quickly threw off his mass vestments and donned his thick, albeit patched, black woollen surcotte, shivering still in the icy air of the little stone church, and teeth chattering like the stones the village boys played with in the summer dust.

They plodded through the snow, lying thick now, several inches deep and just beginning to lose its crispness, like the crust on a newly baked loaf of bread, as the frost lifted over the fields. Their every breath fogged in the cold night air, and offering up a prayer towards the Heavens, he saw the stars as bright as they must have been on that night when the Christ Child was delivered of Mary in a stable, and the brightest of them led the Magi to the Son of God’s humble birthplace, as they carried their expensive presents to offer up worship to him. He had always loved the Nativity story as a small boy, and it had been instrumental in his desire to become a priest; that, and his desire to escape his birth-right in learning.

Father Blaine, who had been out in the world, had taught him how to count, how to read the Bible in Latin and memorise large passages, and how to write in Latin, although there were times when he scandalised even himself by relating the biblical stories and parables in his own rough tongue to his siblings. He could remember clearly the scolding he had received from his mentor and tutor who cautioned against such flagrant contrariness: “Greek and Latin deliver the word of God, my son, not the rude and heathen tongue of the Celts. Never let the monks and friars around the Cathedral hear you, boy”. He had looked at the priest out of the corner of his eye. “And not the Bishop either, Father?” “Especially not the Bishop! Do you want him to send you back to the pigsty?” They had exchanged a complicit smile.

His father, a simple peasant, had been unimpressed with his youngest son,

and, truth to tell, a little afraid of this wayward boy, but his mother, bless her

memory, had never scolded him for his frequent dream-like states,

understanding intuitively her boy’s need to escape the confines of his narrow

life. Father Blaine, that steadfast priest, had gone to the Bishop and asked

for his blessing and help for young Gartnait. The austere figure, so far

removed from Gartnait’s experience of his own tiny world, had agreed, saying, “If you can turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse, Father Blaine, I can do worse than put some coins in the purse.” He had laughed at his own witticism, adding, after a moment: “Throw yourself in the bullock trough, boy, because you smell of the pigsty. Burn your stinking rags and apprentice yourself to Father Blaine. Come once a week to Elgin, to the Cathedral, to learn your letters like a young lordling and improve your Latin and Greek.” The boy had been overcome with gratitude and had run to that surprised, cynical and worldly old man in his Bishop’s robes, and kissed his withered hand. The Bishop had been as good as his word: new clothes had arrived within a few days; extra food rations from the Bishop’s larder; and a little coin to eke out the stipend paid to Father Blaine. He had loved every moment of his apprenticeship, a quick and eager learner, although he did come to understand that the family’s tiny earnings would have to stretch to breaking point without his meagre coin to augment them, and he grieved sorely. His father became less surly when Father Blaine turned over most of the Bishop’s coin to him to cover the loss of his, Gartnait’s, earnings as a pig boy on the land of the local tenant who, in his turn, was bound to the lord. Of course, the lord had to agree to Gartnait’s change of circumstances, too, but he, like the Bishop, was not a hard man, and he promised the boy that he would inherit Father Blaine’s parish and stipend when the old man’s work on Earth was done. He recalled now, in his reverie, how Father Blaine had winked and said: “You might have a long wait.” Gartnait had smiled and answered: “I have much to learn, Father.” The answer had pleased the old man: “Ah, a diplomat, I see.” Fewer than ten years later, he was gone, leaving an enormous hole in the boy’s life, and, at just twenty-one and in his majority, young Gartnait became an ordained parish priest with a ready made congregation who, although they mourned Father Blaine deeply, were glad, he knew, that the young man he had nurtured was to take his place. No village wished to be without a parish priest to bless the crops and the lives that brought them to fruition.

Their footsteps left deep imprints in the snow, the freezing air lifting a little and more flakes falling, and the wind beginning to howl like the Ban Sith, banshee, as they made their way to Marsali’s cottage. A figure, wraith-like and huddled against the wind in a snow-whitened jerkin, and carrying a horn lantern, emerged out of the blinding blizzard that was starting to shriek its wrath and passed on, so close that Father Gartnait would swear to himself later that he felt its ice-cold breath on his cheek. He glanced at Jonet, but that good woman was stooped against the driving snow, intent on reaching her daughter and she seemed not to have seen the figure that had passed so close to her and the priest. Father Gartnait had known him, but not known him, and he stared down at the snow where the figure had trod, terror clutching at his thudding heart with frozen fingers, as if to tear it out of his living chest.

Marsali was not there, and her fire had gone out. Her mother, muttered softly to herself and set about relighting it and building it up, trying in vain to hide her dismay and fear for her daughter, the cold and fear making her fumble and stumble. Perhaps she had gone to visit a neighbour? Just as the flames started to leap and frolic between and over the logs and peats, bringing light and warmth, and dancing merrily as the villagers would do soon to celebrate the Christ’s Mass, they heard a faint mewling sound as if from a kitten, but Marsali had no cat to be birthing in her cottage. Father Gartnait cocked his head to hear from which direction the sound was coming. They stepped carefully to the back end of the house, curtained off by a threadbare woollen screen, where young Alexander and his father had built a small, straw-lined stable for the beasts; from within there they could keep each other and the humans in the cottage warm through the long, bitter winter. That way, all might survive the winter months when the snows piled high and the winds screamed and wailed and threatened to tear both cottage and stable from their anchor in the soil. They could hear the stamping of hooved feet, and the lowing of the cow, her udders full, and desperate to be milked, and the high-pitched squeal of the sow, and the flapping of the hens, unsettled by the cow’s anxious lowing.

5 On a pile of straw, Marsali had brought forth her child, a tiny girl child who was mewling and nuzzling her mother, the cord still attached. Father Gartnait crossed himself and muttered: “Like Our Lady, she has delivered her child in a stable.” Marsali’s mother pushed the priest in the chest: “Father, put the kettle on the fire and heat water to clean Marsali and the child. I need to get them clean and warm.” It was only then that he realized that Marsali and the baby were both covered in blood and mucus, that the cord needed to be severed. He stepped out of the stable, but not before he blessed mother and child, and searched for the kettle, a large bowl already full of water, but iced over. It took Jonet over an hour to clean up her daughter and her grandchild, as she fussed and cooed over the newborn, and, by the time, Father Gartnait peeped in at them again, Marsali was nursing the hungry infant. Jonet was now milking the poor cow, owned in common, with the pig and hens, by the village; it was nuzzling her in bovine gratitude, and all the while, she was glancing worriedly at her daughter. Marsali looked up when she saw him, and her smile held a knowledge that chilled his bones with its Marsali looked up when she saw him, and her smile held a knowledge that chilled his bones with its innocent depth. “He came back to see his child born, Father,” she said. “I told you he would.” She raised her head. “Where is he? Tell him to sleep, Father, and we’ll talk tomorrow when we have both rested.” Father Gartnait stared at Marsali. “Alexander? He is not here, Marsali.” Then gently: “What happened to him? Was he wounded and someone helped him to recover from his wounds and took him home after all this time?” He knew that he was trembling beneath his surcotte and struggled to keep the tremor from his voice. Marsali laughed: “Yes, Father, a very kind lady tended his wounds on the battlefield.” She shifted the child to her other breast. “He talked about the Torwood and the New Park, but I did not know what he was talking of.” She laughed. “He said he had come from a long way away to make sure that we were hale. He looked strange, Father. He showed me his wounds but they had all healed though they were deep and many. He said that he had felt sharp steel pierce his breast and limbs, and that many men, mortally wounded, fell on him and covered him for many days.” She smiled fondly on the child. “He looked at his daughter and said we should call her Mairi after the lady who had tended his wounds so kindly. You see, Father, did I not say that Alexander would come back to us?” She laughed again. “He said that he had seen your candle from very far away and that you were very kind to light it every day for him, and he thanked you for all your prayers.” Father Gartnait shuddered.

He stepped out of the cottage and looked all around. Nothing. Only the swirling snow and the cold wind answered his shout. He stepped back into the cottage and looked at Jonet. “Did you see Alexander, Jonet?” Terror was gripping his mind, befuddling it. Jonet shook her head and rubbed her hands together anxiously, the fear in her eyes reflecting his own. “Have her wits fled for grief, Father? No one had been here before we arrived.” Father Gartnait returned to the stable, to Marsali and her baby. “Marsali, did you mention to… to… Alexander about the candle and the prayers?” She looked at him, puzzled. “No, he seemed to know all about them. That was strange, was it not? He said that we should blow the candle out and not relight it because he could not see it any more and did not need it, and he said that your prayers would light his way if you would keep saying them.” She raised her eyes to the priest. He had had answers for her, her whole life. “He said the lady would look after him.” She hesitated. “Where is Alexander, Father?” Fat tears began rolling down her cheeks and on to the bairn’s head in a parody of the baptism. Father Gartnait knelt beside her and whispered in a stern voice he never used: “You saw your Alexander in a dream, Marsali. In a dream.” She shook her head: “No, Father, he was here.” The priest gripped her shoulders firmly, sensing that Jonet was listening, and including her in his brutal words. “No, it was but a dream, child, a dream. Nothing more. Your Alexander was never here. He fell in the battle. You will not talk of this again, do you hear?” He lowered his voice to a whisper. “There will be no witch burning in my parish.” He remembered now how he had sickened with horrible imaginings, the poor, old creature’s curses ringing in his ears and had lain insensible for two whole days and nights after Father Blaine pulled him from the hideous spectacle all those years ago, a fever consuming him with its hot breath.

Both Jonet and Marsali stared at him, wordless and appalled. The child mewled into the fear-filled silence and opened its eyes – Alexander’s eyes – as blue as the sea in the distant firth, as blue as the summer sky, and a mournful moaning filled the cottage and stable as the cold wind passed through them both, on its way to another place.

6

Elgin Cathedral – named ‘The Lantern of the North’ on account both of its source as a seat of learning and of its specular candles lighting its once-magnificent stained glass windows. It is now a still impressive ruin, having been burned by the Wolf of Badenoch, Alexander Stewart, Alasdair Mor mac an Righ, third surviving son of Robert II

The title – is taken from Genesis, chapter 2, verse 23 (King James Version) and is in juxtaposition to the actual verse and to the biological reality of man being born of woman

Anno Domini – Latin, meaning the Year of the Lord

Christ’s Mass – Christmas

Heretic – religious or social dissenter. Down through the ages, there have always been those who question the orthodoxy of their particular age; the schism between the old Celtic Church and the Roman ensured the Latin Mass

Buain/hairst – harvest in Gaelic and Scots – both spoken at different times in Moray and North-east Scotland, and, prior to that, Pictish

Sasunnach/English – Gaelic/English words for ‘English’, and the Gaelic is not a disrespectful word, merely the word in that language for ‘English’

Andrew de Moray (snr.) – joint Guardian of Scotland with William Wallace, and a brilliant tactician and strategist

Schiltron(m) – massed square of men armed with long pikes, and lethal against heavy horse Spynie – just outside Elgin where Moray’s Bishopric Seat was first situated, and where the Bishop’s Palace of Spynie was also situated

The Laich – large, fertile plain of Moray

Christus Mater – Mary, Mother of Jesus

Wolf’s head – an outlaw

* People in medieval times often lived cheek by jowl with their beasts for warmth, and also to protect the animals from marauders

* Grateful thanks to PublicDomainvectors for illustrations © LornCal 2021

What's Your Reaction?