WHY SINGLE SEX FEMALE SERVICES ARE NOT FOR BIOLOGICAL MALES

This would have been the first of the three articles promised in my last post. However, I’ve revised the original article to incorporate the important speech given this week by the English Attorney General, Suella Braverman, and I’ve divided the original article into two parts. This is the first part and the second will followContinue reading "WHY SINGLE SEX FEMALE SERVICES ARE NOT FOR BIOLOGICAL MALES"

This would have been the first of the three articles promised in my last post. However, I’ve revised the original article to incorporate the important speech given this week by the English Attorney General, Suella Braverman, and I’ve divided the original article into two parts.

This is the first part and the second will follow shortly.

What is a single sex service?

The law on single sex female spaces is set out in the Equality Act 2010, which allows services to be exclusively single sex if this is a “proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim”. I’ll say more about that below.

However, it should already be self-evident that the crucial factor in deciding whether a service should be for one sex only is knowing what “sex” means in this context.

And, as astonishing as it may seem, until very recently no-one did know. This has resulted in the most extraordinary legal confusion as various individuals and groups took a guess at the answer, including the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in their statutory Code of Guidance on the Act.

But now we do know.

In For Women Scotland v Lord Advocate and Scottish Ministers [2022] CSIH 4, the Lord Justice Clerk Lady Dorrian, giving the unanimous opinion of Scotland’s highest civil court, said this:

The protected characteristics listed in the 2010 Act include “sex”….[A] reference to a person who has a protected characteristic of sex is a reference either to a man or to a woman. For this purpose a man is a male of any age; and a woman is a female of any age…. [W]hen one speaks of individuals sharing the protected characteristic of sex, one is taken to be referring to one or other sex, either male or female. Thus [a provision relating to women], as having a protected characteristic of sex, is limited to allowing provision to be made in respect of a “female of any age”. Provisions in favour of women, in this context, by definition exclude those who are biologically male.

In other words, “sex” for the purposes of the Equality Act 2010 means biological sex. If a provision is made in favour of the female sex, it is made in favour of those who are biologically female, and it excludes those who are biologically male.

The court then considered the question of whether the quite separate “protected characteristic” of “gender reassignment” in the Act had any bearing at all on the meaning of “sex”.

Commenting on various previous cases which had been put before them by the parties, the court made clear that these cases did not constitute:

… authority for the proposition that a transgender person possesses the protected characteristic of the sex in which they present.

And to put the matter beyond any doubt, the court continued:

These cases do not vouch the proposition that sex and gender reassignment are to be conflated or combined…

In other words, if a biological male is undergoing what we colloquially call “male to female” gender reassignment, that process will give him the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” under the Act.

But it will have no effect at all on his “sex” for any of the purposes of the Act. His “sex”, for any of the purposes of the Act, will remain male.

The second part of this article will deal with the extraordinary confusion in the law which For Women Scotland has now resolved, with how that confusion may have arisen and with how it has manifested itself in all kinds of ways.

What is important, though – and what you probably didn’t know if you’re not a lawyer – is that as far as the law is concerned, once a court of the highest authority tells you what the law is, then that is what the law has always been.

In other words, since the moment the Equality Act came into force in 2010, the meaning of “sex” for the purposes of the Act has always been the meaning now set out by the court in For Women Scotland – namely, biologically female or biologically male.

Every previous decision of an inferior court, every Code or instruction or piece of guidance which, implicitly or explicitly, proceeded from a different definition from that now provided in For Women Scotland is simply wrong.

Why single sex services are an all-or-nothing deal

In her speech earlier this week, the Attorney General summed up nicely the way in which the Act makes lawful what would otherwise be direct sex discrimination of the most blatant kind. Speaking specifically of schools but in terms which apply equally to services, she said:

The exceptions in [the Act] create a mechanism whose sole purpose is to ensure that even though there is a general prohibition of sex discrimination, [services] are legally permitted to take a single sex approach…. Parliament could not have plausibly intended for these specific exceptions to be subject to collateral challenge by way of complaints of indirect discrimination by other protected groups such as those with reassigned gender. This would be to risk the Equality Act giving with one hand, and promptly taking away with the other.

It is precisely on that basis that, as the Attorney General pointed out, the exceptions in the Act which allow for single sex services:

… permit direct discrimination on grounds of sex: they permit “women only” and “men only” services, provided that the rule is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

In law, single sex services are intended for one sex only: that is the very thing permitted by [the Act]. It follows that it is not possible to admit a biological male to a single-sex service for women without destroying its intrinsic nature as such: once there are [biological males] using it, however they define themselves personally, it becomes mixed sex.

This is the absolutely crucial point, and it is, frankly, a blessed relief to me (and, I’m sure, many others) to see someone of the Attorney General’s status finally making it.

It’s either proportionate and legitimate to have a single sex female service or it isn’t.

It truly is an all-or-nothing deal.

The moment you say that it’s not proportionate or legitimate to exclude even one solitary biological male from your single sex service, then at that exact moment your service ceases to be a single sex service, and you lose your whole justification for excluding any male from that service. When you admit a biological male to what was a single sex female service, you are admitting in terms that you no longer have legal justification for your single sex service. You are now a mixed sex service.

In other words, the justification provided by the Act for directly discriminating against males is not a justification that can be applied only to a few males or to most males or even to the vast majority of males. To retain its validity, it has to be applied to all males.

That is what having a single sex female service is.

The clue is in the name.

Single sex female services not only can exclude all biological males. They must exclude all biological males.

Direct and indirect discrimination

A closer analysis of the detailed provisions of the Act makes this even clearer.

Section 4 of the Act provides that “sex” is a “protected characteristic”.

Section 11 provides that “sex” in this context means “a man” or “a woman”.

Section 212 provides that “man” means “a male of any age” and “woman” means “a female of any age”.

As already noted above, the Inner House of the Court of Session – the highest civil court in Scotland — has now clarified that, for the purposes of the Act, “male of any age” means – and has always meant – biological male, and “female of any age” means – and has always meant – biological female.

Section 13 of the Act provides that it is “direct discrimination” to treat a person with a protected characteristic less favourably than others because of that protected characteristic. For the purposes of the protected characteristic of “sex” this means treating a man less favourably because he is a man or a woman less favourably because she is a woman.

Section 29 of the Act then prohibits a “service-provider” as defined from discriminating in its provision of a service to the detriment of persons requiring the service.

It should therefore be immediately evident that a single sex female service will fall foul of section 13 without some further provision that allows for exceptions to this form of direct discrimination.

More on that below.

Section 19 of the Act provides that, subject to the exception below, it is “indirect discrimination” to apply to a person with a protected characteristic a “provision, criterion or practice” which puts, or would put, the person “at a particular disadvantage” compared to others who do not have that characteristic.

Thus, for example, a “provision, criterion or practice” of a local authority to close all ramped entrances on a block of flats during renovation work could be indirect sex discrimination on the grounds that women are more likely to be the carers of children so that, even although all residents and visitors are denied this access during the work, women are put “at a particular disadvantage”.

The exception which can justify what would otherwise be indirect discrimination is this: if it can be shown that the “provision, criterion or practice” which would otherwise constitute indirect discrimination is “a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim” then it will not be discriminatory.

Sharp-eyed readers will have spotted that this exact phrase, “proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim” has appeared already above in the context of the provisions of the Act which justify single sex female services, and the exclusion of biological males from those services.

More on that below too.

For now, let’s just consider whether section 19, and indirect discrimination, has any relevance to single sex female services.

As already noted above, without some provision providing an exception, single sex services of any kind self-evidently constitute direct sex discrimination of the most blatant kind. So any form of exception for female single sex services will have to justify the blanket exclusion of all males from those services.

Suppose then that there is such an exception and that its terms are met so that a single sex female service is lawfully functioning. If it’s possible for any male to invoke section 19 to say that this lawful direct discrimination against him as a male is also somehow unlawful indirect discrimination against him because he possesses some other protected characteristic such as age or race or religion or gender reassignment, then the whole point of allowing the direct discrimination is lost.

That is to say – again – that single sex services are an all-or-nothing deal. If section 19 could somehow be invoked to allow a male into a female single sex service because he is, say, old or white or Christian or undergoing gender reassignment, then there is simply no point in making any exception for single sex services in the first place. As soon as any male is more disadvantaged than any other male by being excluded, your single sex female service is gone.

As the Attorney General has quite rightly pointed out, that cannot possibly have been the intention of Parliament.

In light of what the court has told us in For Women Scotland, then, any reading of section 19 which would have the effect of converting a single sex service into a mixed sex service is simply unsustainable.

How and why the Equality Act allows single sex spaces

As already noted above, section 29 of the Act imposes a duty on service providers not to discriminate against those with protected characteristics.

In the case of providers of single sex female services, the relevant exception to that duty can be found in paragraph 27 of Schedule 3 of the Act.

Paragraph 27 provides that if any one of six conditions is satisfied and if the provision of services to only one sex is “a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim”, then section 29, so far as relating to sex discrimination, is not contravened.

In other words, if a single sex female service can satisfy one or more of the conditions and can show that excluding all males is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim, then that service will not be discriminating against any excluded male on the ground of sex.

For the reasons given above, that service will not be discriminating either against any male on the grounds of any other protected characteristic that any male may possess because otherwise there would be no point in having the exception in the first place.

This is precisely the point that the Attorney General was making when she said:

In law, single sex services are intended for one sex only: that is the very thing permitted by Schedule 3. It follows that it is not possible to admit a biological male to a single-sex service for women without destroying its intrinsic nature as such: once there are [biological males] using it, however they define themselves personally, it becomes mixed sex.

Regarding the six conditions and the justification of being proportionate and having a legitimate aim for a single sex female service, I’m pleased to say that this is one of the few aspects of this whole area which is not controversial. What is required to satisfy one of the conditions – for example, that a person of the female sex might reasonably object to the presence of a person of the male sex – is well-established, as are legitimate aims such as maintenance of decency, privacy and dignity.

The architecture of Schedule 3 in general and paragraph 27 in particular is also instructive.

It cannot be emphasised enough that the clear – and sole – intent of paragraph 27 is to make lawful what would otherwise be direct discrimination against the opposite sex.

It is highly significant that, as noted above, paragraph 27 achieves this by providing for single sex services exactly the justification of proportionality and legitimacy that is provided in section 19 for the justification of indirect discrimination.

In doing so, it effectively treats direct discrimination and indirect discrimination as one, and makes both forms of discrimination lawful if the single sex justification is established.

And it has to do this.

Because if it were legally possible for any male to establish that a single sex female service had discriminated against him on any grounds such that he had to be included in the service, then the single sex female service would by definition lose its justification for being a single sex service.

Gender reassignment

Paragraph 28 of Schedule 3 provides as follows with regard to single sex services:

A person does not contravene section 29, so far as relating to gender reassignment discrimination, only because of anything done in relation to a matter within sub-paragraph (2) if the conduct in question is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

(2) The matters are—

…

(c) the provision of a service only to persons of one sex.

Before the court’s clear decision in For Women Scotland, this was an obscure and highly controversial provision. Now, it isn’t.

Firstly, for the purposes of single sex female services, the provision must apply to biological females who are undergoing gender reassignment. If a single sex service were to exclude a so-called “transman” from its female services on the grounds, say, that her beard and deep voice were “triggering” for rape victims, that is clearly an exclusion made because of her gender reassignment.

As such, it clearly requires justification under paragraph 28 and, if justification cannot be established, it will equally clearly be direct discrimination against the protected characteristic of gender reassignment.

Secondly, it may be arguable that a biological male in possession of a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) under the Gender Reform Act of 2004 (GRA) falls to be regarded as acquiring some form of legal fiction which allows him to be classed as a “biological female” for the purposes of the Equality Act.

In Fair Play for Women Ltd v The Registrar General for Scotland and The Scottish Ministers [2022] CSIH 7, the highest civil court in Scotland said this:

There are some contexts in which a rigid definition based on biological sex must be adopted.

And this:

Some of these limitations have been carried over to apply even where a person has successfully obtained a GRC under the GRA….The point which these examples all have in common is that they concern status or important rights.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s a pity that the court didn’t say more about where exactly a GRC fits into the definition of “biological female” for the purposes of the “status” and “important rights” conferred by the Equality Act.

My own interpretation of these statements is that a biological male with a GRC remains a biological male for the purposes of single sex provision and that there is no need to invoke paragraph 28 of Schedule 3 to exclude him, along with all biological males, from single sex female services.

If I’m wrong about that, and if paragraph 28 does require to be invoked in order to exclude a biological male with a GRC from single sex female services, then that will in my view have serious consequences for the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill currently making its way through the Scottish Parliament. I’ll deal with that in detail in the last of the forthcoming articles.

(Spoiler: if having a GRC does turn a biological male into a “biological female” for the purposes of the Equality Act, then it is simply absurd for the Scottish Government to claim, as they do, that the Bill’s provisions allowing biological males to obtain a GRC by essentially self-identifying as female do not intrude into the reserved area of the Equality Act. Clearly, they do, and as such the Act, if passed, will be struck down by the courts as outwith the competence of the Scottish Parliament.)

Whence all the confusion then?

If the legal position on single sex spaces is as clear and rational as I have tried to set out above, why then has there been so much confusion and uncertainty on the topic?

That will be the subject of the second part of this article but I’ll give another quick preview here.

In my opinion, the reason for the confusion is simple, and it extends to the commentary on the Act itself, to the EHRC’s statutory Code and its various attempts at more informal guidance and even, as I’ll seek to show, to at least one English judicial decision.

Before For Women Scotland, many people – including many lawyers, and even some judges – wrongly believed that the protected characteristics of “gender reassignment” and “sex” under the Act were to be conflated, and that any person undergoing gender reassignment was to be treated as being of the “gender” to which they were reassigning.

And, crucially, by “gender”, they meant “sex”.

I hope you’ll come back for this second part and for the other two articles which set out the evidence for this belief and the consequences of its being held so widely, in appropriate detail.

Longstanding – and longsuffering – readers of this blog know that this may not be as soon as I presently intend but I hope you’ll find it worth the wait.

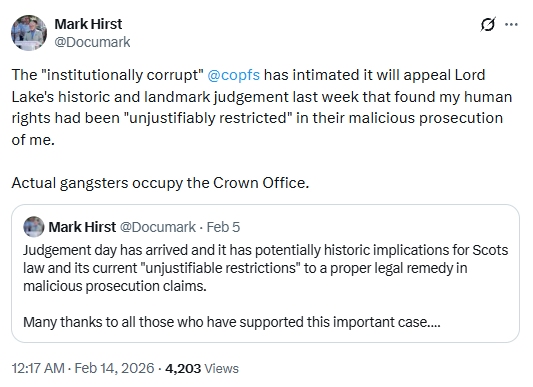

What's Your Reaction?