Reality Bites

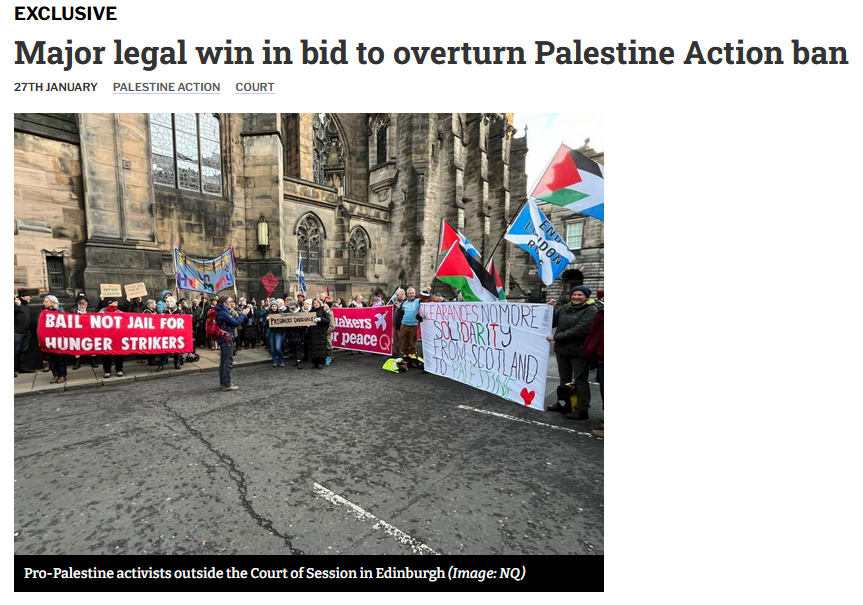

On 23 March 2020, Mr Salmond walked out of court after a jury found him not guilty of twelve charges, one charge had been found not proven, and one other had been dropped by the prosecution earlier in the trial. Alex Salmond had sat in court for two weeks as his future and his freedom were weighed on the scales of justice. In the end he walked out of the Edinburgh court a free man; not one of the two charges of attempted rape, nine of sexual assault, and one of a breach of the peace had been proven. Regardless, then, of anyone’s opinion or their feelings on the matter...

Tweet Follow @Jeggit

By Jason Michael

IN THE OPEN SOCIETY we are each entitled to our own opinions, but one thing we are not entitled to are our own facts. From about the middle of the twentieth century postmodern critiques of social and political structures and of language have emerged from the academy and have percolated through society and culture which have fundamentally challenged our understanding of reality – and the consequences of this have not always been good. René Magritte’s clever and iconic painting, ‘The Treachery of Images (1929),’ with its image of a pipe and the slogan, Ceci n’est pas une pipe (‘this is not a pipe’), very much captures the postmodern and poststructuralist approaches to semiotics – the relationship between signs and symbols to language and understanding – that would take shape in the new philosophies of the post-war era. Yet, at the same time, it presaged a deep crisis in hermeneutics which would become apparent in the popular and hypermodern philosophies of the twenty-first century; post-truth and the death of meaning.

We have created a world in which logical contradictions may exist – even in the same mind – and both still remain in some meaningful-meaningless way true.

Of course, Magritte was right. This image of a pipe is not a pipe, it is a representation of a pipe – a meaning-bearing sign or symbol which, like all artistic representation, is open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation. In a sense, then, his pipe is a nothing. It is a nothing awaiting transformation into a something through the subjective gaze of the viewer. Ultimately, the statement he is making is that ‘reality,’ whatever that is, is surreal:

The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So, if I had written on my picture ‘This is a pipe,’ I’d have been lying!

As if mocking the Cartesian dogma of existence as a product of thought, surrealism in art and the ideas of postmodernism and poststructuralism reduced thinking itself to the absurdity of the radical subjectivity of thought. For as many thinkers as there are, they suggest, there are individual realities – nothing can be objective. It is this assault on truth, therefore, that sets the scene for the wired non-philosophy of the early twenty-first century; the absolute individuality of perception, thought, and reality. We have created a world in which logical contradictions may exist – even in the same mind – and both still remain in some meaningful-meaningless way true.

Why have we started this article with an apparent word salad of strange cerebral psychobabble? Well, for the simple reason we have just seen it in action in the re-trial-non-re-trial of Alex Salmond, the former First Minister of Scotland, and we have seen how individuals’ perceptions, thoughts, and realities have clashed with the old realities of reason, law, fact, evidence, and objectivity. In the most disturbing and divisive way, we have witnessed how people’s emotions and individual experiences and biases have formed hard facts and realities out of thin air, regardless of the solid facts of the situation – and the result is complete and utter chaos.

Regardless, then, of anyone’s opinion or their feelings on the matter, according to the law, Mr Salmond is innocent.

On 23 March 2020, Mr Salmond walked out of court after a jury found him not guilty of twelve charges, one charge had been found not proven, and one other had been dropped by the prosecution earlier in the trial. Alex Salmond had sat in court for two weeks as his future and his freedom were weighed on the scales of justice. In the end he walked out of the Edinburgh court a free man; not one of the two charges of attempted rape, nine of sexual assault, and one of a breach of the peace had been proven. Regardless, then, of anyone’s opinion or their feelings on the matter, according to the law, Mr Salmond is innocent. But this fact did not deter his successor, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, remarking to the press during a COVID-19 briefing:

The behaviour [the women] complained of was found by a jury not to constitute criminal conduct, and Alex Salmond is innocent of criminality. But that doesn’t mean that the behaviour they claimed of didn’t happen.

Here is the problem. The complainants in the case claimed that Mr Salmond had either attempted to rape them or that he sexually assaulted them. In law, when a jury finds someone not guilty, it means that it did not happen. When a jury – in Scotland – finds a charge not proven, it means that the evidence was not sufficient to prove beyond reasonable doubt that it did happen. The law, however, has its limitations. Every day people are denied justice in courts, and every day there are miscarriages of justice. It is an imperfect system. So, Ms Sturgeon is correct; just because the court found Alex Salmond not guilty, does not mean that the events as the women testified to them did not happen. But this also implies the opposite; just because a court finds someone guilty, does not mean the events as the witnesses reported them did actually happen. We can play this game all day, and this is one of the reasons why we must leave these questions to the determination of the courts.

It is perfectly alright for us here to toy with these hypothetical abstractions, but it is not alright for a head of government to do the same at a press conference. It is unethical for an elected leader to cast doubt on the verdict of a court, and, for Ms Sturgeon, this is a serious violation of the ministerial code of the Scottish parliament. A Scottish court arrived at a not guilty verdict, and so, for the First Minister, the verdict is not guilty – it did not happen. Neither can she hide behind the language of evidence and testimony being found to not constitute criminal conduct.

Under the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009, both attempted rape and sexual assault are acts of criminal conduct, and these were the charges brought against Mr Salmond. This is to say, attempted rape and sexual assault cannot be committed up to a point not constituting criminality. Either it is attempted rape and sexual assault or it is not. The court determined that Alex Salmond did not commit attempted rape or sexual assault. And it is not for the First Minister to speculate on the possible limitations of the court’s decision in any particular case. This is not her job, and for her to sow the seeds of doubt in the public mind is wrong.

Attempted rape and sexual assault cannot be committed up to a point not constituting criminality. Either it is attempted rape and sexual assault or it is not.

Yet, getting back to that pipe that is not a pipe, for Nicola Sturgeon, her identity politics, coupled with the magisterium of her own opinion, this speculation constitutes a kind of transcendent truth. She can cast doubt on the decision of a court because in her mind the court may have made a mistake. Time and again in this case – and in other similar cases – we have encountered the feminist identity politics slogan ‘Believe Women.’ Such a maxim points to the special nature of women as victims, whose weaker position within the ‘patriarchy’ makes it more difficult for them to receive justice, and who, therefore, we must simply believe. While this call to trust women reporting sexual violence is based on a reality – the fact that women do find it difficult to receive justice in the courts, it is an emotional and not a rational claim. Justice cannot and will not give preferential treatment to one group over another. This would not and could not be justice. Even with all it’s limitations, the law demands evidence, testimony, and the interpretation of evidence and testimony.

Simply and uncritically believing anyone or any particular group who reports a crime itself creates injustice. If we are to ‘believe women’ in rape and sexual assault cases, then – as a matter of faith and not reason – we must believe them no matter the verdict; as is the case right now against Alex Salmond. No matter the decision of the court, then, to ‘believe women,’ means that in a meaningful-meaningless way the accused may still have committed the crime and is therefore guilty by accusation. In no sense can this be described as justice.

What this is, is a hyper-individualistic truth claim arrogating to itself the offices of judge, jury, and executioner. Rather than justice, this is vengeance stemming from a particular identity politics which seeks retribution for the real and perceived crimes and injustices committed upon and felt by this one victim group – women – against an imagined oppressor group – men. The precedent it sets is awful, and the effect only makes victims of individuals of the so-thought oppressor class. Men and boys accused of rape or sexual assault can never under any circumstances, even innocence, be innocent – because the limitations of the system will always mean the accused might have done it. Such a perverse reality, in fact, dispenses with the law altogether. What need is there of a court and a legal system when everyone accused is guilty by accusation?

Men and boys accused of rape or sexual assault can never under any circumstances, even innocence, be innocent – because the limitations of the system will always mean the accused might have done it.

It is here that the intellectual and artistic experiments of surrealism and postmodernism must be separated from what is in actual fact real and solid and verifiable. Thought experiments have their limitations too, and we would do well to bear this in mind. Mr Ramsey, my old Physics teacher at Kilmarnock Academy, taught me one of the greatest philosophy lessons I have ever had. He described, in a lesson on motion and velocity, how some ancient Greek in a toga had described the impossibility of any object in motion ever completing a journey from one point to another. If this object is to go from point A to point B, he said, it must first get from point A to a point half way between point A and point B. And if it is to go from point A to a point half way between point A and point B, it must first travel from point A to a point half way between point A and the point half way between point A and point B. On and on it goes, having to complete smaller and smaller tasks ad infinitum and so never being able to complete its full journey from A to B.

In theory, the old Greek was right. But in practice … well, in practice Mr Ramsey clambered on top of a workbench with a rugby ball, saying, ‘Let my foot be point A, and let the wall at the back be point B.’ With a mighty punt, the ball made it all the way from A to B and then to C, and through C (‘C’ being the classroom window). And with that smashing of glass the thought experiment was put in its place. In the real world, we cannot escape the fact that reality bites.

Scottish National Party leader speaks after Commons walkout

What's Your Reaction?