A Maritime Vision for an Independent Scotland

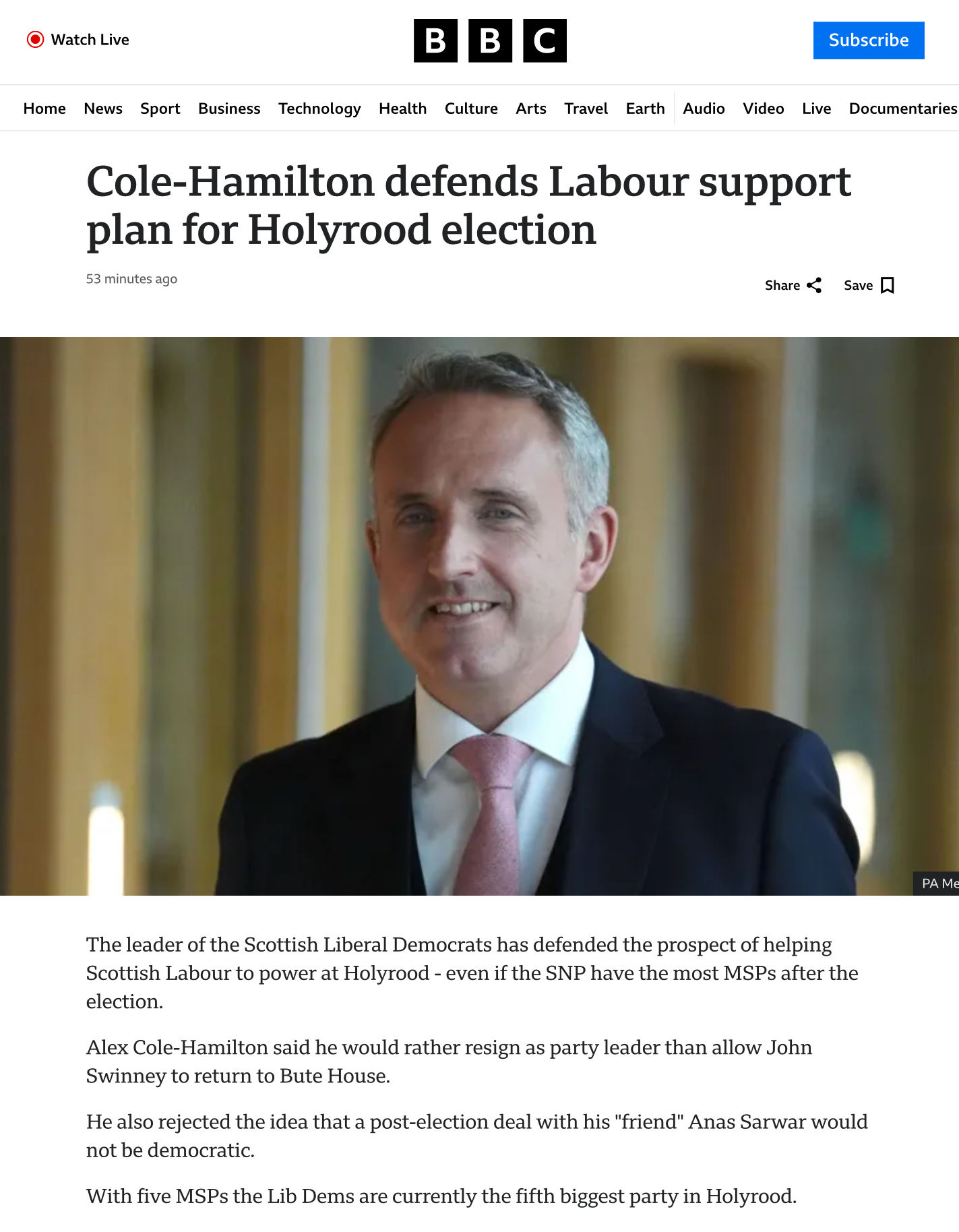

Professor Alf Baird sets out the case to bolster Scotland's maritime network and says current policymakers won't ‘rock the UK boat’ when it comes to maritime policy in Scotland.

Our world is full of former imperial-run colonies that are now independent countries. The leaders of those plundered and exploited countries had no choice but to develop a new confident vision for their people as independent sovereign states. As global trade and hence economic development depends on maritime transport it should come as no surprise that most of these ‘new’ independent countries focused heavily on maritime policies and related projects to drive economic growth and prosperity. In places such as Dubai and Singapore, Ireland and Estonia, and many others besides, the port and maritime sector quickly became the main driver of the economy.

By contrast, Scotland’s maritime transport infrastructure currently sits moribund, mostly useless, certainly visionless, squeezed between our own crumbling colonial-like legacies and Tory sponsored regulatory capture. Look at what remains of our long-since derelict and obsolete major city-ports on the Firths of Forth, Clyde and Tay, where most of the port infrastructure was built when Queen Victoria reigned. These massive yet now largely unused and outdated maritime assets are today owned and regulated ‘Tory-style’ by non-transparent, offshore private equity financial engineers masquerading as port authorities.

Alf Baird was Professor of Maritime Business at Edinburgh Napier University. He has a PhD in strategic management in the global container shipping industry and is a former ship agent for international shipping lines.

These entities have no vision for our country, nor are they tasked with developing Scotland’s international competitiveness; their priority is securing profits from exploiting private port monopolies whilst investing as little as possible in a decayed and outmoded asset base, inevitably leaving a diminished economy in their wake. The remainder of Scotland’s mid-size ports adopt another rather English ‘trust’ style of ownership and regulatory model (as opposed to the Latin or public port model on the continent) which likewise invariably serves the interests of trustees and private interests instead of the public good.

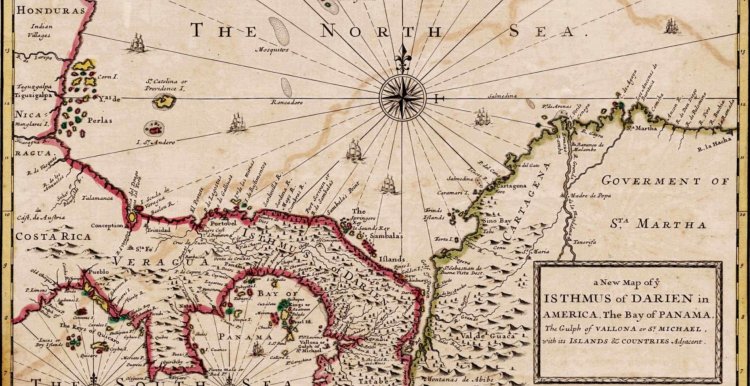

All of this economic dysfunctionality remains devoid of any national shipping policy, something arguably last seen in Scotland around the time of the Darien Scheme in the late 1600’s. Which brings us back to the present reality consisting of Scotland’s outdated obsolete seaports, an embarrassing lack of sophisticated, frequent international shipping connections with the outside world (Ireland has several daily ferry services to the continent, Scotland has none), our worsening international competitiveness as a result, and a stalled and declining long-term trade position. All of this reflects on failed or inadequate UK policies which are still pursued today and constrain Scotland’s development, now made worse by Brexit, even under devolution and an inept ‘Scottish’ Government still run by UK civil servants who aye adhere to Whitehall diktat when it comes to the UK’s international maritime priorities. In this sense Scotland’s distinct international maritime needs and opportunities are never considered, never mind prioritised. In the UK context we remain a peripheral ‘devolved’ region, very much colonial-like; plundered and exploited, for sure, and prevented from developing and reaching our true potential as we would seek to do if an independent state.

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing New Caledonia, a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s.

The remedy? The vision? Scotland clearly has little option but to focus on selectively developing its national strategic seaport infrastructure aimed at improving competitiveness and expanding international trade, as all former colonies had to do, including Dubai, Singapore, Kenya, Malaysia, Oman, India, Malta, Ireland and many others. ‘In the beginning it was the harbour that made the trade’, as any first-year student of maritime economics knows, and without ports trade cannot flow and economies are unable to grow. My own research has identified two major national strategic port priorities and opportunities in Scotland: at Cockenzie/Preston Links on the site of the former power station which would be aimed at developing intra-European trade, the latter now made more critical by an enforced Brexit, and; the unique natural deep-water harbour of Scapa Flow positioned at the crossroads between North Sea and Atlantic Ocean aimed at handling and ‘intercepting’ global container transhipment covering a wide array of markets. Combined, these two maritime infrastructure initiatives could easily and rapidly double (or more) Scotland’s current lacklustre levels of international trade, and at relatively limited expense.

Whilst both port schemes are modest by international standards, they represent a minimum start to enable an independent Scotland to get back on the global shipping scene and to develop trade. Both can be progressed quickly using the standard international port concession model offering long-term tenancies to the preferred global terminal operating companies who would themselves make much of the investment in partnership with the public sector port owner, the latter acting as regulator. This is totally unlike the Tory sell-off privatisations and regulatory-capture ‘model’ that continues to burden Scotland, in ports as it does in other strategic ‘utility’ sectors such as energy, and airports. Both port projects involve brownfield, public-owned sites and would make positive use of existing available landside areas, as well as benefitting from proximity to deep water.

And what about developing Scotland’s international shipping connections? Again, not a difficult challenge given the right expertise and knowledge, also employing the international concession/tendering approach where appropriate. The EU Motorways of the Sea (MoS) policy and processes, which I had some part in developing for the European Commission, can be readily used to attract and select ferry lines to introduce long-term services connecting Scotland with the continent, Scandinavia and elsewhere. The same concession approach may also be used to modernise our island ferry services which badly need new tonnage, and to help develop new urban public-transport ferry services on Clyde, Forth and perhaps also the Tay, the latter an opportunity ignored, yet common internationally. Other independent countries, many of them ex-colonies, have no difficulty doing all of this and much more, so why should Scotland? The experience of numerous former colonies, now independent countries enjoying vibrant maritime economies demonstrates their can-do attitude, with national liberation providing the freedom to act in the national interest for a change, to set the national vision, instead of constantly being held back from development by imperial diktat. Scotland for now remains stuck in the latter mode, in a colonial rut.

Modern catamarans in Bergen city harbour, variations of which could be used for Forth and Clyde urban ferry services, as well as Firth of Clyde and elsewhere.

Modern catamarans in Bergen city harbour, variations of which could be used for Forth and Clyde urban ferry services, as well as Firth of Clyde and elsewhere.

And if Scotland really wants to develop shipbuilding capability, again all we need is a can-do pro-active international strategy to be pursued. How can Norway and other countries replace over 100 ferries in the last decade whilst Scotland’s poorly led devolved public agencies within the UK, devoid of expertise or vision, cannot even build two boats? Some of the best global ship designers I have worked with are Scots (forced to do their business outside our homeland), yet Scotland’s public bodies have ignored their proposals to build proven ferry designs in Scotland, proposals I helped put together. Scotland needs around 100 new ferries in the next 20 years, which should be viewed as an excellent opportunity to kickstart the shipbuilding industry and allow us to develop the ability to compete in international markets too. These ships could be built in Scotland, on the Clyde and at BiFab’s excellent Burntisland site, but this requires the right strategy, expertise, commitment, and national vision, all currently lacking in our limited ‘devolved’ public sector which still retains a UK mindset and policy focus.

The ongoing fiasco in Scottish shipbuilding, which was rightly described as ‘catastrophic’ according to Holyrood’s REC Committee in respect of CMAL/Ferguson’s, must be remedied, and quickly. Scots ship design specialists are building large numbers of proven ferry designs in Asia and elsewhere, yet our public bodies rejected their offer to do the same here? Instead, our public sector has put in place the usual sort of people who do not have the right skills, international expertise or competence, or vision to develop our shipyards and public maritime agencies properly, which will inevitably lead to further problems. This must change, the people must change, the right global shipping expertise should be deployed and brought in where necessary, and the vision must alter markedly if Scotland is to break free from an enduring colonial-like control and mindset and its inherent industrial development limitations.

A small, specialist, focused Scottish maritime agency established by government is what is needed to start to take forward a new positive maritime vision and to deliver on these ideas, and others. We could start now, but the UK civil service still running Scotland’s institutions continues to play by UK rules when it comes to international maritime matters, and a devolved Holyrood has been unable to alter that. The current policy makers won’t ‘rock the UK boat’. Which means that independence will most likely be necessary before any comprehensive maritime vision for Scotland, such as is briefly set out here, can be fully taken ‘on board’ and delivered, as was the case in many former colonies. And even then, positive change can only happen if the right strategy and structures, and most importantly the right people with the necessary expertise, passion and vision for Scotland are put in place.

In 2020, Alf published a research-based academic textbook on the subject of Scottish independence: 'Doun-Hauden: The Socio-Political Determinants of Scottish Independence': Buy it here.

What's Your Reaction?