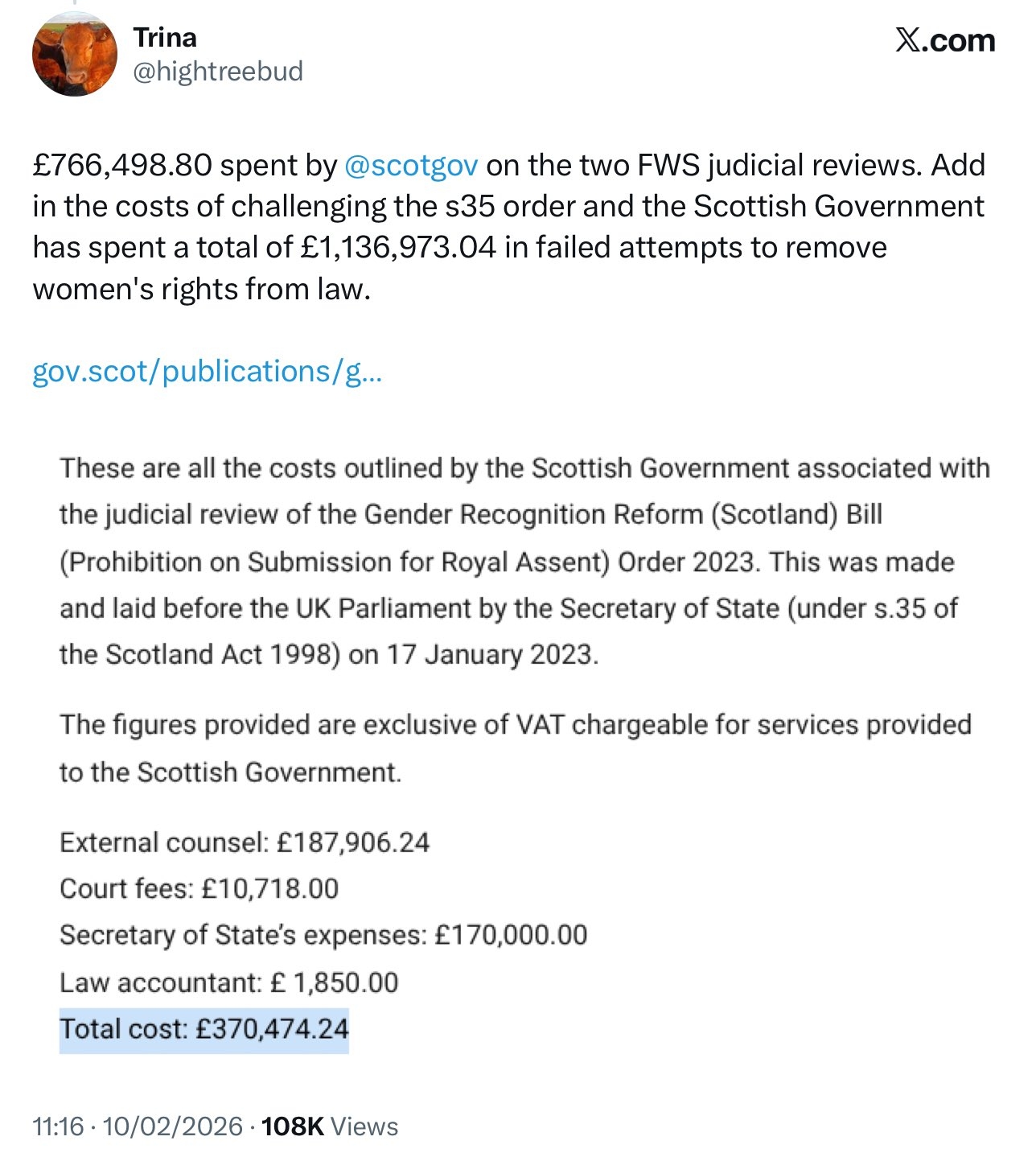

Steve Norris letter to the ICJ over the Supreme Court Ruling.

This is the letter Steve Norris sent to the International Court of Justice seeking information on how Scotland could challenge the ruling from the Supreme Court in England. Tomorrow I will publish the response he received from the ICJ. I am a senior Scottish journalist investigating possible legal and political steps open to Scotland following the NovemberContinue reading "Steve Norris letter to the ICJ over the Supreme Court Ruling."

This is the letter Steve Norris sent to the International Court of Justice seeking information on how Scotland could challenge the ruling from the Supreme Court in England. Tomorrow I will publish the response he received from the ICJ.

I am a senior Scottish journalist investigating possible legal and political steps open to Scotland following the November 23 decision of the Supreme Court in London.

The ICJ is no doubt aware that Lord Reed found against the Scottish Government, ruling that despite having a democratic mandate to hold a referendum on Scottish independence in October 2023, Holyrood did NOT have the ability to do so without the consent of the UK Parliament.

The reason given by Lord Reed was that even a consultative referendum would have legal force by virtue of the fact that a Bill enabling it would have been passed by the Scottish Parliament.

That status, he explained, meant that such a referendum could have direct consequences for the union between Scotland and England and, because the constitution is a policy area reserved to the United Kingdom parliament, would therefore be outside the competency of the Scottish Parliament and ultra vires.

The verdict. predictably, was greeted with some consternation in Scotland: protest rallies were held across the country that evening along with similar events in several European cities, notably Munich, Berlin and Rome.

Speakers highlighted how the decision ran contrary to the long established Scottish constitutional tradition of popular sovereignty – namely, that power, ultimately, rests with the people, and not, as is the case in England, with the Crown-in-Parliament.

It was forcefully stated that the Scottish people, by majority vote in the Scottish General Election of May 2021, instructed the Holyrood government to hold an independence referendum: therefore, in order to honour their democratic wishes, one must be held, without fear or hindrance.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court decision discarded that aspiration, effectively closing off a lawful and democratic route to that referendum.

That is, of course, unless the UK Government agrees to transfer the required consent – something it has made abundantly clear it will not do – or another authority intervenes to rule on whether the Supreme Court’s decision accords with international law.

The ruling shattered a few illusions in Scotland – the most important being that the country was a partner in an entirely voluntary union – a belief previously and publicly reiterated and endorsed by UK Government Ministers on many occasions.

The verdict has exposed the truth of Scotland’s status – or at the least the truth as the UK state sees it – with the result that previous UK Government assurances regarding the union’s voluntary nature are now widely regarded as having been false, even deceitful.

The Scottish Government has stated that the court’s findings have profound implications for the proper functioning of democracy in Scotland, not least because it raises the question of whether there is ANY democratic route out of the union with England at all.#

In short, the country, both in effect and in reality, appears to many to be trapped in a constitutional prison – with the UK Government holding the keys.

This perception that this locking in of Scotland is neither fair nor just is widely held, and not only by supporters of Scottish independence.

Another point worthy of note is Scotland’s unique constitutional status in Europe and the world.

The Kingdom of Scotland was one of the two co-signatories to the 1707 Treaties of Union (the other being the Kingdom of England) which gave rise to the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the first place.

Under international law, therefore, the ability of Scotland to dissolve that union, as with any political divorce, has always existed in theory, should the majority vote for it.

Relevant also is the country’s unique constitutional history: Scotland is Europe’s oldest integral kingdom, has Europe’s oldest fixed frontier and was an independent state for almost 1,000 years.

Moreover. two famous historical documents enshrined its concept of popular sovereignty: the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320 – centuries ahead of its time – and the 1689 Claim of Right, both reserving to the people the right to remove their rulers should they act contrary to their interests.

Scotland therefore bears no comparison to any other territory on earth, not the Chagos Islands, not Quebec, not Catalunya and certainly not Kosovo.

The United Nations Charter upholds a nation’s right to self determination – and the Supreme Court made reference to this.

But Lord Reed held that because Scotland is “not a colony”, is not “oppressed” and has “access” to the UK government and the levers of power, the argument invoking the United Nations Charter, and specifically its self-determination clauses, falls.

However, that interpretation to many appeared perverse.

Lord Reed’s first point on Scotland not being a colony is arguably true (with serious caveats), but the third, although having some superficial substance de jure, is in truth de facto a misrepresentation of reality, given the Westmister parliament’s cursory dismissal of Holyrood’s wishes ever since the 2014 independence referendum.

However, it is Lord Reed’s second point, that Scotland is not “oppressed”, which is widely regarded as being of doubtful merit.

His reasoning seems blind to the fact that Scotland’s democratic voice has been consistently ignored, even contemptuously ignored, since 2016, when the country overwhelmingly voted to remain in the European Union, but was removed from the bloc against the popular will.

Subsequently, insult was added to injury, in terms of democratic deficit, during long and disputatious negotiations with the EU, when the country’s government in Edinburgh was excluded from any meaningful involvement in those talks.

Most notably, the UK Government deliberately raised a legal challenge in the Supreme Court against the Scottish Government’s 2018 EU Continuity Bill designed to align all devolved competencies with EU law – despite the Bill having been already passed by Holyrood.

During the delay, the UK Government rushed through its own legislation which supervened the Holyrood Bill, rendering it redundant – an egregious action referred to by Scottish Ministers as “constitutional vandalism”.

Even more importantly, at several Scottish national elections the ruling Scottish National Party, won a succession of mandates from the people to hold an independence referendum.

The last – and strongest – of these came in the May 2021 Holyrood elections, where independence-supporting parties won 72 seats to the unionist parties’ 57 – a majority of 15.

Pro-independence parties also won an outright majority of the popular vote.

One glaring anomaly therefore arises with regard to the November 23 Supreme Court decision, and it is this: if one partner in a bipartite union consistently and egregiously denies the right of the other to walk away, what is that if not “oppression”?

Is it not the case that Scotland is being “oppressed” through being denied the democratic right to decide its constitutional future?

In the eyes of many, the Supreme Court ruling is a ludicrously narrow interpretation of the self-determination rights conferred on nations by the UN Charter.

My questions, therefore, are these: firstly, its “sub-state” status notwithstanding (although it is worth bearing in mind that both Ukraine and Belarus, despite holding sub-state status were UN members alongside the USSR from 1945-91), would Scotland, through legal representatives of its elected government, have recourse to the International Court of Justice with a view to seeking a ruling on whether the Supreme Court judgement is fair, just and compliant not just with international law, but with the UN charter itself and, equally as importantly, in accordance with the spirit of the articles of the charter governing the right of nations to self-determination?

Secondly, given the country’s unique constitutional history and status outlined above, would the ICJ be prepared to look favourably on at least considering a plea from Scotland on a non-precedential basis, the current grounds for hearing a grievance under “contentious cases” or ” advisory proceedings” notwithstanding, on whether the nation has the right to hold a referendum on its constitutional future in accordance with the wishes of the people?

I look forward to your response by Burns Day, January 25, if possible.

Le durachdan (regards),

Steve Norris

Senior Reporter

Galloway News

What's Your Reaction?