THE MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

A guest post from Stuart Rodger. The missed opportunities On the drizzly, grey morning of the 19th September 2014, as Scotland was coming to terms with having voted No to independence the night before, no one could have known just how propitious the circumstances for a second plebiscite – with more favourable chances of success –Continue reading "THE MISSED OPPORTUNITIES"

A guest post from Stuart Rodger.

The missed opportunities

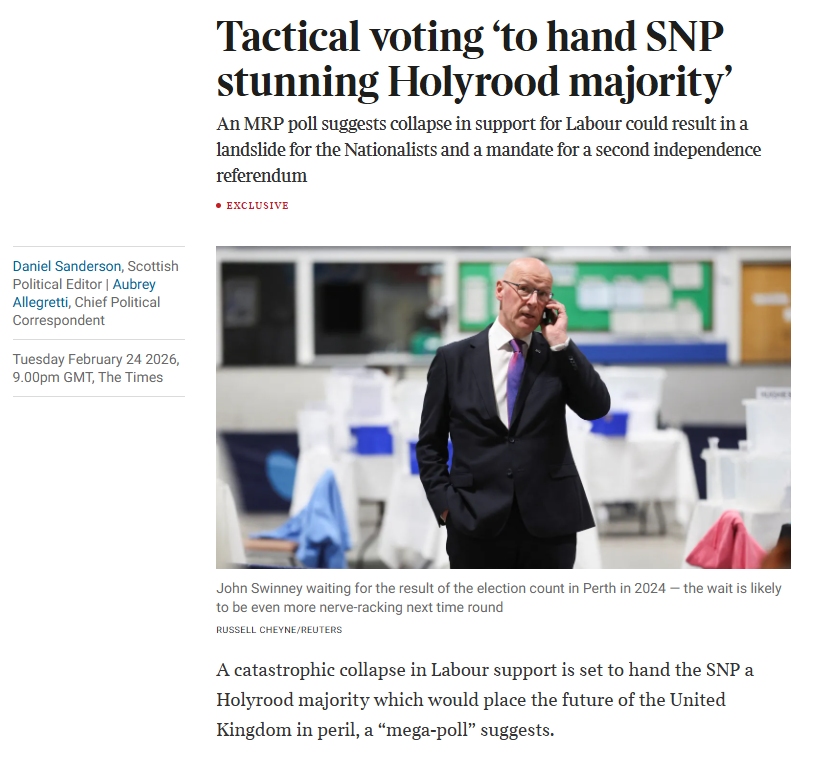

On the drizzly, grey morning of the 19th September 2014, as Scotland was coming to terms with having voted No to independence the night before, no one could have known just how propitious the circumstances for a second plebiscite – with more favourable chances of success – would soon become. But seven years on, Scotland is no closer to independence, in any real legal sense, than it was on that characteristically dreich Scottish morning in 2014.

As Scotland heads towards a fresh parliamentary election – and with the spectacle of Alex Salmond’s new political party on the scene – it’s worth examining the opportunities missed for Nicola Sturgeon to turn a second referendum into a reality, and put Scotland on a path to its historic departure from the United Kingdom.

**

Within days of the lost 2014 vote, membership of the SNP had surged to over a hundred thousand members, taking it to third place in the UK as a political party by size of membership. Nicola Sturgeon packed out The Hydro concert hall in Glasgow with over 10,000 gushing activists, giddy with renewed determination and devotion to the cause. Within eight months, the SNP rode into Westminster on a tsunami, winning 56 out of 59 Scottish constituency seats – a political spectacle many of us never thought we’d see in our lifetimes. And then, on the 23rd June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, while every Scottish local authority had voted to stay. It felt like the union was about to go bang.

After months of faux compromise – Sturgeon had advocated a special Scottish Deal, but everyone knew this was unlikely to come to pass – the much-anticipated call for a second referendum duly came on the 13th March 2017.

But there was a problem, a problem Scottish readers will by now be quite familiar with but which readers from elsewhere perhaps less so. The conventional reading of the law as it stands – specifically the Scotland Act 1998 – is that constitutional affairs, and the Union itself, are reserved to Westminster. Schedule 5 of the Act states that “the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England” is a reserved matter, but provides an avenue for the temporary transfer of such powers under Section 30 of the same Act.

Theresa May said No. “Now is not the time”, to be precise. Everyone waited with baitedbreath for Nicola Sturgeon to pull something out of the bag in response.

But Sturgeon didn’t budge. She didn’t move. After weeks of waiting it became clear what her strategy was: stand back and use the moral and democratic force of her cumulative mandates: the 2015 Westminster landslide, the 2016 SNP win, and then the Brexit vote, dragging Scotland out of the EU against its will. To this day, Sturgeon maintains that refusal to grant permission for a second referendum is “unsustainable” and that those who stand in the way of democracy “get swept away”. It begs the question, was Sturgeon right to do this, or was she, as some critics have suggested, “asleep at the wheel”? What real opportunities were there to politically arm-twist Westminster to grant Scotland its referendum?

Three opportunities are discernible.

Opportunity one came in the form of a potential legal challenge on the question of constitutional competence. This would have involved the Scottish Government legislating for a referendum, and then the asking Scottish Court of Session, and then the Supreme Court, to arbitrate on whether the Scottish Parliament alone had the power to enact the legislation. There are those who think such a challenge would be dead on arrival. But others disagree, suggesting that the Scottish Parliament may well have the power to hold a legal referendum, but that Westminster would merely be under no real legal obligation to legislate and enact the result, with only a political obligation to do so.

This seems to be the essence of Aidan O’Neill QC’s position on the matter, who drew up a legal opinion on this question for a grassroots effort, led by Martin Keatings, to have this question tested in court, arguing: “if the avowed purpose of the Scottish Parliament in legislating for a further independence referendum is simply to consult the people of Scotland only about possible future constitutional change… then this may be said to be predicated on an acceptance that any fundamental change in the terms of the current Union between the Kingdoms of Scotland and England is a matter ultimately for the Union Parliament to make.”

If that had failed, opportunity two came in the form of the result of the 2017 General Election, which gave the SNP some measurable bargaining power in the House of Commons. A deal could have been struck between Nicola Sturgeon and Theresa May, whereby the SNP would have provided the crucial votes to vote through her Brexit Deal in exchange for a Section 30 and Westminster’s green light for a referendum. Despite being unquestionably controversial, there would have arguably been a certain political elegance to it, given that it would have respected both mandates – the mandate for Brexit, and the mandate for a second independence referendum. Granted, it would have been improbable for May to sign up to this, but so desperate was May to go down in history as the PM to deliver Brexit that the idea cannot be dismissed off hand.

Had that failed, opportunity three came in the form of a plebiscitary election. The proposal is that the SNP would be going into the looming May election with a stripped down manifesto, declaring that a vote for it – and possibly any other pro-independence party – would be a vote of endorsement on the question of independence itself. The intervening time between a failed offer of a deal with Theresa May and the looming election could have been used to a draw up a blueprint for the infrastructure of an independent state. Such a blueprint could have been launched somewhere symbolic, like Rosyth, in Fife – a touted location for a Scotland-EU trading port after Scotland re-joins the bloc.

But instead, Sturgeon has lit a slowly defusing bomb underneath the party, pursuing wildly divisive policies like Gender Self ID, which many women regard as a threat to their sex-based rights, and oppressive hate speech laws, which were roundly criticised from groups as disparate as the Scottish Catholic Church and the Scottish Secular Society. So much of the campaign for independence is about capturing the imagination and the possibilities of what Scotland could be, but Sturgeon has refused to talk up the possibilities of independence for years now. Even the pandemic hasn’t changed that, but instead reinforced it.

More than that, she has moved the SNP from centre-left to solidly centrist turf: ditching radical land reform, endorsing the neoliberal agenda proposed in the Growth Commission,and aligning with the hawkish side of American foreign policy.

There is only one final, more charitable explanation for Sturgeon’s inaction over the past five years, and that is that she is merely playing the long game. She herself has said, in an interview with The Scotsman last year to mark her 50th birthday: “the Yes movement possibly has something to learn about the fact that – as we have stopped shouting about independence, and shouting to ourselves about how we go about getting independence, and just focused on [dealing with the pandemic] – it has allowed people to take a step back and say: ‘Well, actually that’s the benefit of autonomous decision-making’ and also ‘perhaps things would be better if we had a bit more autonomous decision-making,’”

Cynics may suggest this is self-serving: as a strategy it conveniently helps to shore up the SNP’s devolved power, while absolving them of the responsibility of grasping the thistle and actually delivering independence. In this analysis, the SNP does not exist for independence, but the idea of independence exists for the SNP, and gradualism has become unionism. But others point to the opinion polls, which arguably vindicate her: of the last 30 opinion polls, 23 of them have recorded a majority for Yes.

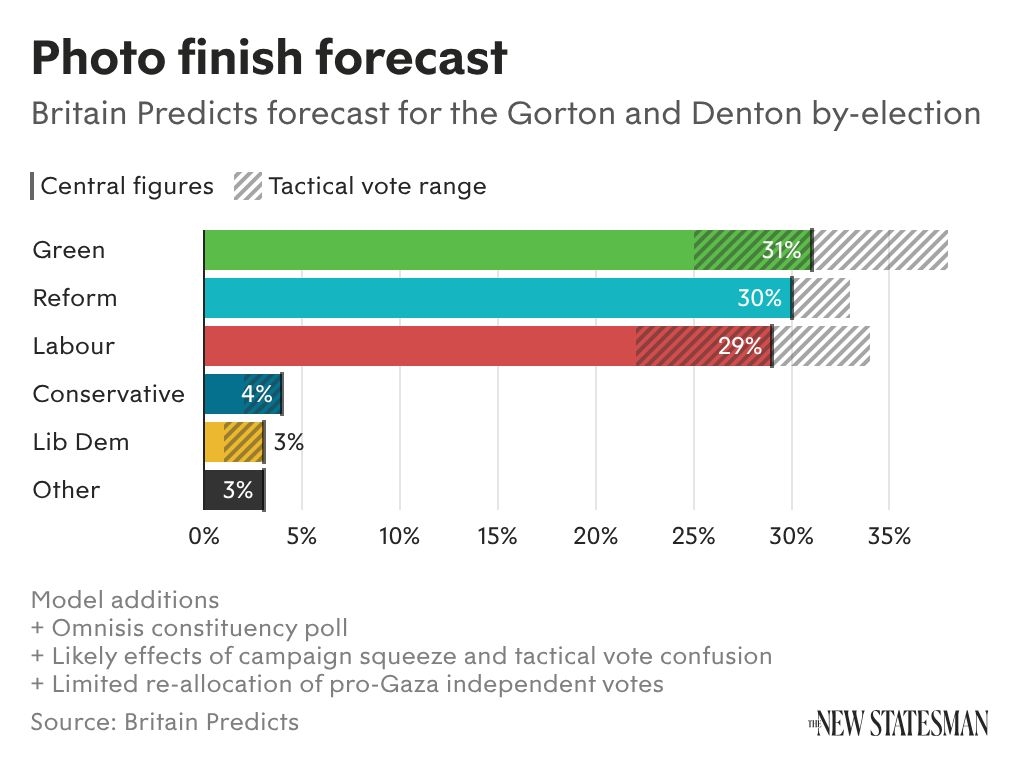

But with the launch of Alex Salmond’s new Alba Party, which is seeking to win SNP voters’ second vote on the regional list and thereby help build a supermajority for independence, it is clear that patience in the movement is at literal breaking point. The set-up of other minor parties – the Independence for Scotland Party and Action for Independence – were already indicative of a restlessness in the movement boiling over. The achievement of a supermajority, if it happens, will generate ferocious political pressure in and of itself. Even more thrillingly, however, is that should court challenges uphold the status quo, a parliament with a two-thirds majority can choose to dissolve – opening the door to a plebiscitary election as a democratic alternative to a referendum.

In truth, the problems in Scottish politics can arguably be boiled down to a very prosaic explanation, which is that expecting one political party, in the form of the SNP, to sustainably carry 50% of the population is unhealthy and simply unrealistic. Of course 50% of the population have divergent, and strongly held, views on the economy and social policy, and indeed the type of independence to be pursued. The animosity and rivalry of Nigel Farage and Dominic Cummings proved a successful formula for delivering Brexit, a dynamic and winning Leave versus Leave campaign. Could the same happen for Scottish independence, with Yes versus Yes?

The prize for the independence movement is within sight. The election of the next parliament will show us whether it can yet be grasped.

References • “swept away”: https://www.thenational.scot/news/18908324.nicola-sturgeon-johnson-will-swept-away-like-trump-denies-democracy/• “unsustainable”: https://www.gov.scot/publications/first-minister-statement-brexit-scotlands-future/• “if the avowed purpose of”: https://security-eu.mimecast.com/ttpwp#/checking?key=c2luZGkubXVsZXNAYmFsZm91ci1tYW5zb24uY28udWt8cmVxLWVlZmM2OGU4Y2VjOTA0OGVhNWU2MzEwOTNmOWMyNzg0• “the Yes movement possibly has”: https://www.scotsman.com/news/politics/big-interview-nicola-sturgeon-resilience-party-unity-and-turning-50-2917739• “of the last 30 opinion polls”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_on_Scottish_independence

What's Your Reaction?