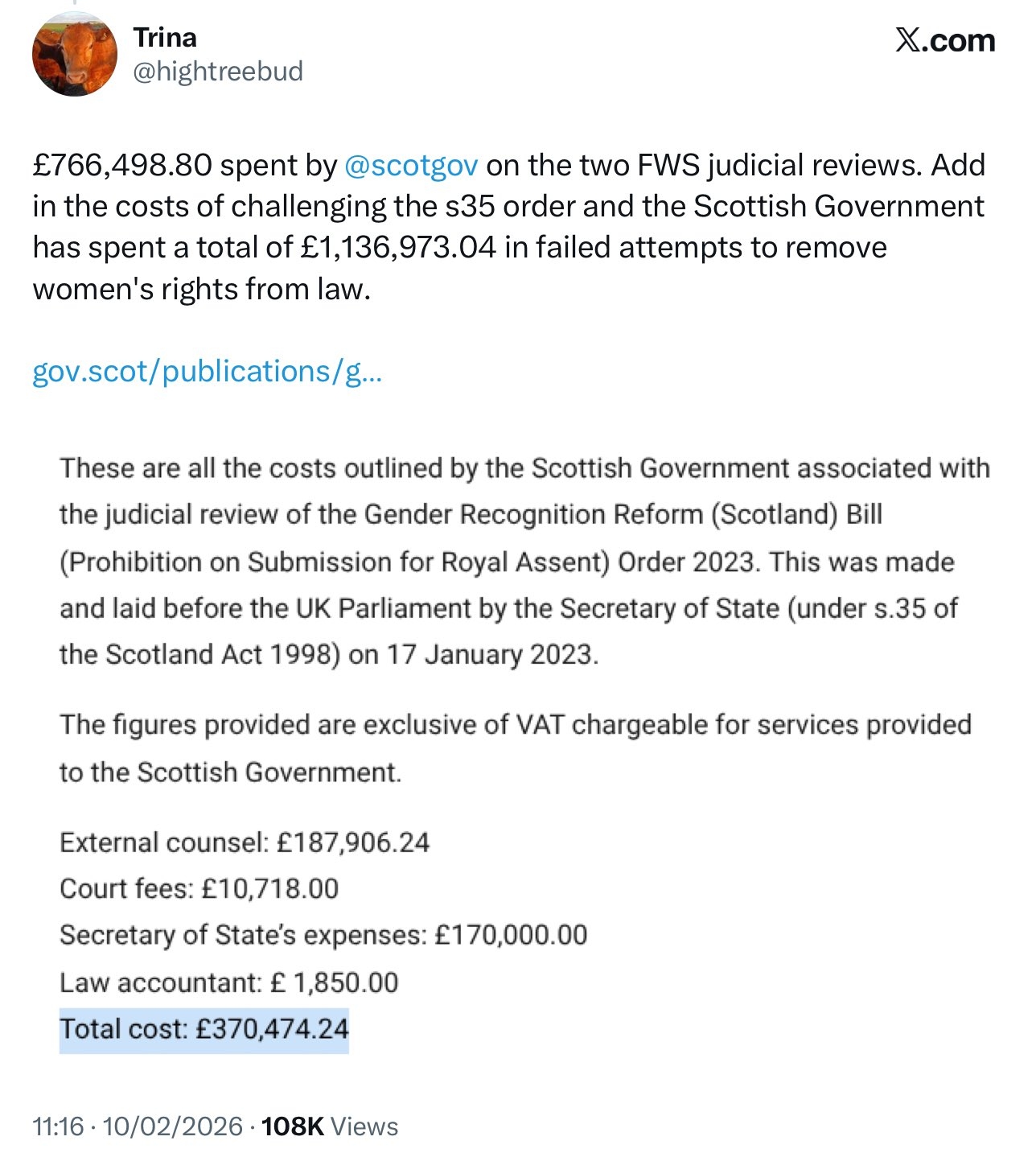

WELL SHOULD IT?

This article was originally published by its author William Thomson on the Scotonomics website. The Scottish National Investment Bank should it invest in carbon projects run by asset management firms based outside of Scotland? Is the Scottish National Investment Bank’s investment strategy what most Scots think or expect? Here are a few questions and answers toContinue reading "WELL SHOULD IT?"

This article was originally published by its author William Thomson on the Scotonomics website.

The Scottish National Investment Bank should it invest in carbon projects run by asset management firms based outside of Scotland?

Is the Scottish National Investment Bank’s investment strategy what most Scots think or expect? Here are a few questions and answers to set the scene.

Q: Should Scotland’s National Investment Bank (SNIB) support a project whose investors do not pay any income tax on their earnings? Considering the role of a public bank, most people would say no.

Q: But what if the project sequesters carbon and contributes to a net-zero and just transition? Then probably most people would say yes.

Q: But what if that support was funding £10 million of public money per year for five years to an asset management firm that is also the UK’s largest commercial forestry business based in England? Maybe not then.

Q: And what if it hadn’t yet actually purchased any forests in Scotland? Hmm.

Q: Also, the carbon credits generated can be used for “insetting” the practice that allows investors to purchase credits instead of reducing carbon emissions. Then that’s different.

Q: What if the project did not pay the community that housed or was negatively affected by the project? Oh, hold on a minute.

The Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) was launched in November 2020. It has three parts to its mission (i) Place; (ii) Net Zero; and (iii) Innovation (1). Under its Net Zero mission, it has to date, funded one project involved in carbon sequestration. The Bank has a total capitalisation of 2 billion pounds over ten years. It has committed to invest £50m over five years to the Gresham House Forest Growth & Sustainability LP; a fund set up to purchase plantations of Sitka spruce with the anticipation of sequestering 1.2m tonnes of CO2 in twenty years (1).

Gresham House Asset Management is the largest forestry investment manager in the UK, managing £1.3 billion of UK forestry assets (2). The traditional forestry business of selling timber will underpin the fund with carbon credits seen as ‘topping up’ the fund.

SNIB’s investment is exceptionally important to the fund. Both the SNIB CEO and the Managing Director of Forestry, Gresham House Asset Management, highlight the role of SNIB funding in ‘crowding in’ private investment (3): where their public money goes, private capital will follow. So the first question to address is, is this the type of investment SNIB should be making?

To investigate further, let’s return to those six questions.

1. Should Scotland’s national investment bank support a project whose investors do not pay any income tax on their earnings?

Currently, the tax system governing the fund’s income is run by the UK Treasury. The Scottish Government has no control over how the profits are taxed. Should Scotland become independent, the Scottish Government may change how it taxes income in Scotland, but that would not affect this investment as it is based in London.

Most people would find it bizarre that investors do not need to pay any income tax on the profit from their investment. As discussed in our Incentives for a Just Transition blog post, the UK Government believes or has been persuaded that companies and wealthy individuals need additional incentives beyond normal market conditions to make these types of investments. Gresham House forecast that global timber consumption will rise by 170% by 2050 (1). Paying no tax is a spectacular incentive and, as we argue here, entirely unnecessary.

So the Scottish Government could say it is not investing in projects that do not return something to the public purse. Still, considering the UK sets the tax system, it would mean that it could not invest in any commercial forestry businesses because as well as no income tax for investors, commercial timber businesses do not pay any corporation tax.

Suppose, however, a community or a social enterprise ran a commercial forest. In that case, SNIB could invest, safe in the knowledge that the investment was returning to the public purse as social enterprise redistributes or reinvests their profits. So SNIB could invest in forestry that was returning something to the public, assuming those types of projects were available. But SNIB is choosing not to do that.

Investing in this fund, SNIB is bringing more private investment into the land market. As Mirian Brett and Laurie Macfarlane covered in their research for Community Land Scotland, this is causing the Scottish land market to inflate (4).

2. But what if the project sequesters carbon and contributes to a net-zero and just transition?

Forests will play a crucial role in a net-zero carbon economy. Their role in a just transition is much more complicated. And if the credits are used for “insetting”, then it could be argued that they are simply supporting corporations to continue to pollute. So even what looks like a positive move by SNIB has its issues. Not anyone can invest in this fund. The minimum investment is £91,830.

3. But what if the bank contributed £10 million of public money per year for five years to an asset management firm that is also the UK’s largest commercial forestry business based in England?

Should SNIB encourage asset management companies to purchase Scottish forests ahead of local communities or Scottish-based businesses? As much of our natural capital should be owned in Scotland as possible.

4. What if it hadn’t purchased any forests in Scotland yet?

At the moment, the fund hasn’t purchased any land in Scotland. As argued above, this might not be bad, but it again points us to question the investment in “Scotland” by SNIB.

5. The carbon credits can be used for “insetting” the practice that allows investors to purchase credits instead of reducing carbon emissions.

Insetting is like offsetting, but you don’t need to go through the hassle (or expense) of buying credits as “insetting” means you own them. Offsetting and insetting have significant issues, as discussed by George Monbiot.

The fund enables investors to either sell the carbon credits (without paying any income tax, remember) or to use them to offset their emissions. They should only be used for residual emissions; however, if you have already paid for them (insetting), it becomes costly NOT to emit the carbon you have already paid for. And, of course, there are only certain types of businesses that can afford insetting. Many more projects will likely be used for insetting, jeopardising the decarbonisation of the economy.

6. What about if the project was not paying anything to the community that housed or was located to the project?

When a piece of green infrastructure, for example, a wind turbine, is created, a payment is supposed to be paid to the local community at the rate of £5000/MW installed capacity per year (5), in part for the hassle in construction and maintenance, and in part to embed sustainable development into the project.

To follow this through, couldn’t SNIB make this suggested payment conditional on its investment in any green investment projects? As the Scottish Forestry Strategy 2019-2029 (6) highlighted:

as the economic contribution of Scotland’s woodlands and forests grows, the risk of possible negative effects on local communities and their environments also increases. For example, greater visitor traffic and timber transportation could potentially impact on communities, particularly if the rural transport network is not adapted to accommodate these changes in use.

The Scottish Government has already argued for more community support and involvement in forestry projects, but it seems it doesn’t what that to get in the way of a financial return.

Perhaps the salient point is that underpinning this investment is the spectre of more land consolidation. It would be hard to argue that supporting projects like this will do anything other than further exacerbate Scotland’s position as the European country with the most inequitable land ownership, where 500 individuals own over 50% of Scotland’s private rural land (7).

So let’s take another look at this £50 million investment. This investment is currently not impacting Scotland in any meaningful way. When it does, it is likely to negatively impact the land market and local communities. The credits can be used to inset emissions instead of leading to meaningful carbon emissions. When the profits are delivered, the Government takes no share. More Scottish land is held in the hands of wealthy investors.

Is this what we hoped and expected from the Scottish National Investment Bank?

What's Your Reaction?