A VERY SCOTTISH COUP (PART ONE)

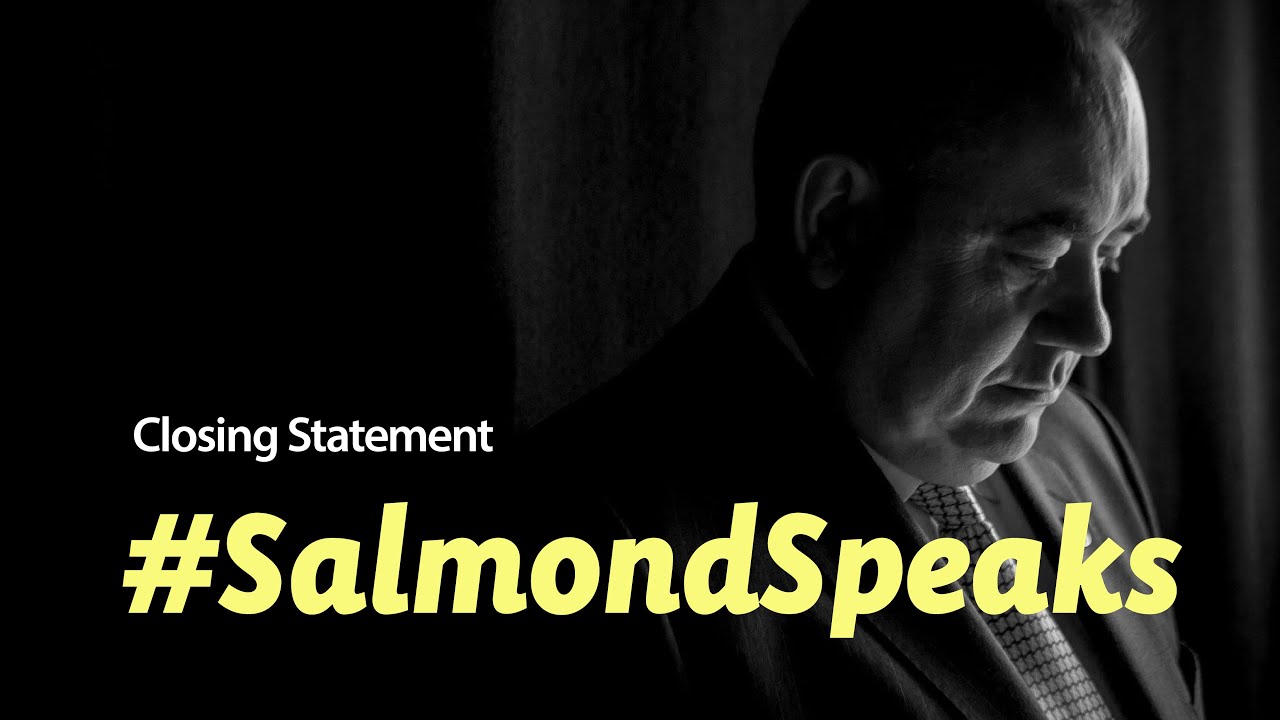

Let me be clear, as the First Minister herself likes to say. I don’t think Nicola Sturgeon was being truthful when she made this statement to the Scottish Parliament on 10 January 2019 about the complaints against Alex Salmond: “I did not know how the Scottish Government was dealing with the complaint, I did notContinue reading "A VERY SCOTTISH COUP (PART ONE)"

Let me be clear, as the First Minister herself likes to say.

I don’t think Nicola Sturgeon was being truthful when she made this statement to the Scottish Parliament on 10 January 2019 about the complaints against Alex Salmond:

“I did not know how the Scottish Government was dealing with the complaint, I did not know how the Scottish Government intended to deal with the complaint and I did not make any effort to find out how the Scottish Government was dealing with the complaint or to intervene in how the Scottish Government was dealing with the complaint.”

I think it’s inconceivable that Nicola Sturgeon did not know of the complaints against Alex Salmond as soon as they were made in November 2017.

I think it’s inconceivable that Nicola Sturgeon did not then direct personally the development of the unlawful procedure which was devised by her civil servants specifically to target Alex Salmond.

And I think it’s inconceivable that Nicola Sturgeon was not closely involved in the unlawful handling by her civil servants of the complaints against Alex Salmond from the moment they were made.

I therefore think that Nicola Sturgeon has committed a flagrant breach of this most basic requirement of the Ministerial Code:

“It is of paramount importance that Ministers give accurate and truthful information to the Parliament…. Ministers who knowingly mislead the Parliament will be expected to offer their resignation….”

I think that the First Minister should have resigned a long time ago.

But suppose I’m wrong about all of that.

Suppose Nicola Sturgeon has actually told the truth to the Scottish Parliament, and in the pleadings lodged on behalf of her Government and herself in the Court of Session.

And suppose that every civil servant who has given evidence to the Fabiani inquiry has told the truth too.

Then I think that, if anything, Nicola Sturgeon and her civil servants are in even worse trouble.

Because if they are all telling the truth then there has been, and continues to be, a coup of the most unprecedented proportions against the democratically elected First Minister and democratically elected Government of Scotland by unelected civil servants.

And the First Minister and her Government, who have stood by and let that coup happen, are every bit as much to blame for it as the civil servants who carried it out.

The Civil Service Code

It seems almost pedantic to mention rules at all in the face of such a blatant and self-evident coup against democracy but, perhaps not surprisingly, developing and executing a policy targeted exclusively against a former First Minister behind the backs of the present First Minister and her Government turns out to be in breach of the Civil Service Code.

This is what the Code requires of civil servants under the heading of “Honesty”:

“You must not… deceive or knowingly mislead a minister…”

This is what is required under the heading of “Objectivity”:

“You must … provide … advice to ministers on the basis of evidence, and accurately present the options and facts.”

And just in case that isn’t clear enough:

“You must not … ignore inconvenient facts or relevant considerations when providing advice or making decisions.”

It’s worth at least bearing those rules in mind as we explore the civil servants’ own accounts of what they did behind the First Minister’s back in November and December 2017.

Scottish Government policy on alleged sexual harassment by former Ministers in November 2017

This can be stated simply. In common with every other democratic government in the world, the Scottish Government had no policy on alleged sexual harassment by former Ministers in November 2017.

So if ever there was an area in which civil servants should not have been acting on their own initiative, and behind the backs of their Government, it was this one.

But then perhaps, even if there was no actual policy, there was at least some hint from the First Minister or her Government that could give civil servants, determined for some reason to go it alone, some kind of guidance on how to do so.

Well, let’s look at that.

On 31 October 2017, the Cabinet of the Scottish Government provided its civil servants with a “commission” – a formal instruction – which was recorded in the Cabinet minutes under the heading of “Sexual Harassment” as follows:

“While there was no suggestion that the current arrangements were ineffective, the First Minister had also asked the Permanent Secretary to undertake a review of the Scottish Government’s policies and processes to ensure they were fit for purpose.”

Not much encouragement here, then, for our independent-minded civil servants to strike out on their own.

There was, in terms of the commission itself, “no suggestion that the current arrangements were ineffective”. If then the current effective arrangements did not include procedures for progressing specific allegations against a former First Minister who also happened to be the present First Minister’s mentor and, by her own account, the closest person to her outside of her own family for thirty years, perhaps that was a rather obvious signal that, at the very least, the present First Minister must be advised of these allegations before another step was taken.

In fact, let’s get even more specific.

If the Permanent Secretary Leslie Evans thought on receiving these allegations against Alex Salmond in November 2017 that, alone among all the governments of the world, the Scottish Government needed a new and unprecedented procedure to deal with them, she was obliged by the rules of her job, as well as by plain ordinary common sense, to bring the allegations to the attention of the appropriate Government Minister, namely the First Minister.

If Leslie Evans truly thought that the Scottish Government’s policies and procedures were not fit for purpose unless they could deal with these specific allegations, and that new policies and procedures were therefore needed, it was incumbent upon her to provide all of the evidence in her possession about the allegations to the First Minister, to advise the First Minister on the basis of that evidence, and to accurately present the options and facts.

By the same token, Evans was expressly forbidden from deceiving or knowingly misleading the First Minister and from ignoring inconvenient facts or relevant considerations by withholding this vital evidence of the specific allegations from her.

Our hands-on First Minister and the Ministerial Code

Could there have been, though, some analogous policy or procedure for dealing with similar allegations in another context that Evans could have claimed to be applying in this novel context? And could that have excused what looks for now like the most flagrant of breaches of the Civil Service Code?

Well, let’s look at that too.

The only arguably analogous policy to which Evans could have turned for support in dealing with the Alex Salmond allegations without any mention of them to the First Minister or her Cabinet was the policy for dealing with allegations against current Ministers, namely the policy laid out in the Ministerial Code.

I’ve written and talked about the relevant provisions of the Ministerial Code in previous posts but, with apologies to regular readers, here they are again:

“The First Minister is … the ultimate judge of the standards of behaviour expected of a Minister and of the appropriate consequences of a breach of those standards.”

And:

“It is not … the role of the Permanent Secretary or other officials to enforce the Code.”

That seems pretty clear. Even if we grant for the sake of argument that Evans could rely on an analogy with allegations against current Ministers in seeking to deal with the allegations against Alex Salmond in November 2017, there is precisely nothing in the Code which would have allowed her to do so behind the back of the First Minister.

The Ministerial Code says so in terms. It is for the First Minister to judge the standards of behaviour expected of Ministers. It is for the First Minister to decide whether there has been a breach of such standards. And, where the First Minister decides that there has been such a breach, it is for the First Minister to decide what the consequences for the Minister are to be.

And, as the Code also makes clear in terms, not one of those things is a matter for the Permanent Secretary.

But matters go further still.

The civil servants cliped on their own coup

There was specific communication between senior civil servants on this very topic in November 2017 which puts beyond any doubt that Evans and her colleagues knew full well that all allegations of sexual harassment against Ministers were to go straight to Nicola Sturgeon the very moment they were received.

Remember that the first allegations against Alex Salmond were made in a phone call from complainer Ms B to Director of Communications Barbara Allison on either 7 or 8 November 2017. (The Scottish Government’s Written Statement says 7 November but Allison told the inquiry on oath that it was 8 November.)

Allison then told Evans of the allegations on 9 November 2017.

Just days later, on 13 November 2017, Cabinet Secretary James Hynd said this in an email to senior civil servants about sexual harassment allegations against current Ministers:

“We would need to alert the FM to the fact that a complaint had been received against one of her Ministers and to take her mind about how she wished it to be handled.”

On 15 November 2017, Hynd was even clearer. Here he is, in an email sent to both of Evans’s private secretaries, commenting on a suggestion that complaints against Ministers might be resolved by informal means without the need for Sturgeon to be involved:

“I am not at all sure that this … will be acceptable to the FM either generally or in the specific context of sexual harassment. Especially for the latter I think she will want to know straightaway if a complaint against a Minister has been received and will want to decide how it should be treated.”

There is, then, not the slightest plausible argument that Evans or any of her fellow civil servants could possibly have thought that it was acceptable for them to keep Nicola Sturgeon in the dark about any allegation of sexual harassment against any of her current Ministers.

What possible legitimacy, then, could attach to their extraordinary decision not to tell her about such allegations against her mentor and closest friend of thirty years?

None that I can see.

Nor do matters end even there.

At exactly the time Ms B’s allegations against Alex Salmond were being made to Barbara Allison and passed on to Leslie Evans in November 2017, senior civil servants in the HR Department were coming up with a “route map” for allegations of sexual harassment against former Ministers.

It’s clear that they were simply making this up as they went along since the Cabinet commission of 31 October 2017 had made no mention of the need for any such “route map” and there was no existing policy or procedure for former Ministers on which it could possibly have been based.

Nonetheless, its terms are worth noting:

“If allegation is about a former minister … FM to be alerted …”

And on 15 November 2017, the same date on which he made clear to all of his colleagues the need for Nicola Sturgeon to be advised the moment any allegations were received against a current Minister, Hynd also circulated to all the key players his proposed policy for dealing with sexual harassment complaints against any former Minister.

The draft contained this paragraph:

“The Permanent Secretary will be advised at that point [when a complaint is received] about the nature of the complaint. If the former Minister is a member of the Party of the current Administration the First Minister will be informed and will decide how to address the complaint against the former Minister.”

It’s quite bizarre. Even in terms of their own policy – the one they were now dreaming up from thin air, and entirely behind the backs of the First Minister and the Government they were supposed to be serving – Evans and her fellow civil servants were acknowledging that the first step they should be taking with the Salmond complaints was to tell Nicola Sturgeon about them.

Having acknowledged this obvious requirement on them, they then proceeded to blithely ignore it until June 2018, when the First Minister herself finally told them she had known of the complaints since 2 April.

It’s hard to know whether to be more baffled by their rule-breaking or by their ineptitude.

But perhaps we need to bear in mind that Leslie Evans, over and above any policy of the Government she works for, is an enthusiastic personal devotee of the Stonewall cult and its unhinged policy of “acceptance without exception”, as are other key players such as Nicola Richards and Judith Mackinnon.

So these are people who think that a man can turn into a woman – no, really – just by ticking a preference for female pronouns on a form, and that saying women are “adult human females” is a “dogwhistle” for a “transphobic” hate crime.

Maybe nothing should surprise us about this would-be Scottish junta and their utterly extraordinary coup.

PLEASE COME BACK SOON FOR PART TWO OF A VERY SCOTTISH COUP.

WE’RE ONLY JUST GETTING STARTED.

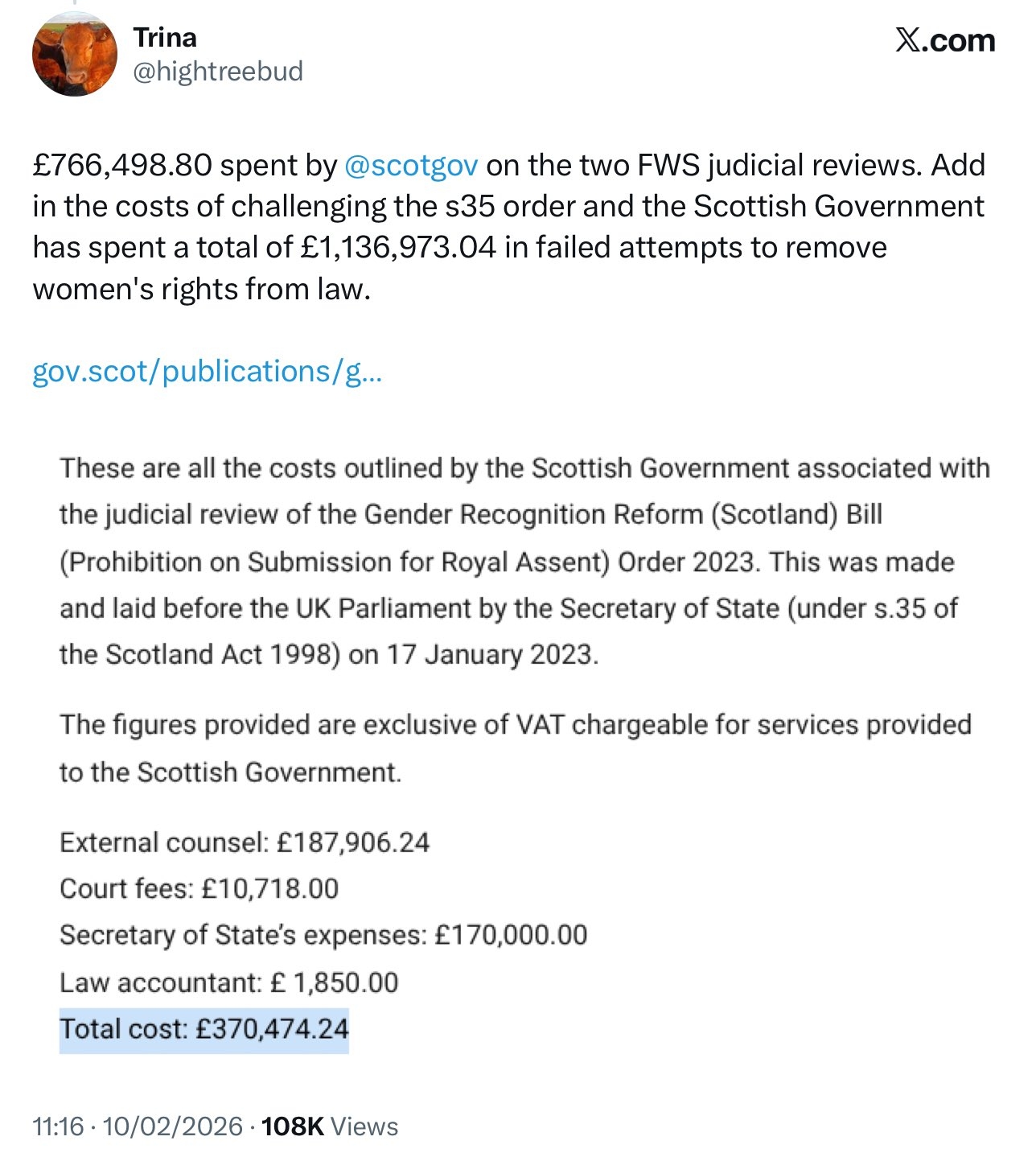

What's Your Reaction?