DECOLONISING THE CLAIM OF RIGHT. A RESPONSE FROM SARA SALYERS.

Decolonising the Claim of Right A Response Sara Salyers I am grateful to this author for the thoughtful, intelligent and careful argument he sets out. It is important to test any theory, political or legal, particularly when it is your own position, so I welcome the opportunity to do so. The errors in the argument – and there are serious errors – stem not from a want of knowledge orContinue reading "DECOLONISING THE CLAIM OF RIGHT. A RESPONSE FROM SARA SALYERS."

Decolonising the Claim of Right

A Response Sara Salyers

I am grateful to this author for the thoughtful, intelligent and careful argument he sets out. It is important to test any theory, political or legal, particularly when it is your own position, so I welcome the opportunity to do so.

The errors in the argument – and there are serious errors – stem not from a want of knowledge or sound reasoning but from unexamined assumptions and interpretations, assumptions so generally held that they are practically received doctrine. But erroneous they are and erroneous they will remain, no matter how widely accepted. Unpicking an argument is a much more lengthy process than setting one out, so this response is inevitably both longer than I would like and limited in scope – or it would be even longer!

The standing of the Claim of Right as a constitutional document is not in doubt.That there *is* such a thing as Scottish constitutional law and that it diverges from English constitutional law is also undisputed. Whatever Lord Cooper’s opinion, (and he was what Professor Sir Neil McCormick called ‘a DaFoeist’ as opposed to a Diceyist), I draw your attention to the last three words of his famous obiter: “the principle of unlimited sovereignty of Parliament is a distinctively English principle and has no counterpart in Scottish constitutional law” (MacCormick v Lord Advocate 1953 SC 396)

There is no constitutional law without a constitution. So where is it? And when, precisely, has the largely uncodified constitution of Scotland been interrogated in the way that the English constitution has been? Where, other than in the Claim of Right, are its terms expressly articulated? And what is the source of what McCormick called, ‘the Scottish constitutional anomaly’?

The Claim of Right Act 1689 not only asserts the existence of a fundamental constitution – upon which the rule of law stands and by which it is upheld and enforced – but some of the legal provisions it cites are distinctly Scottish. Thus it supplies in part, what a codified constitution would provide and, in part, a kind of Rosetta stone for the Scottish constitutional record.

A constitution is, of course, similar to but not identical with the rule of law. And a statute setting out the terms of a constitution as the basis for its effect is also something more specific than a statement of the rule of law. Particularly when the parameters of the ‘rule of law’ itself are so very uncertain in the English/UK context:

“A ‘health warning’ is in order for anyone venturing into this area: a cursory glance at the index of legal periodicals revealed 16,810 citations to books and articles concerned with the rule of law, and that is certainly an underestimation… There is considerable diversity of opinion as to the meaning of the rule of law and the consequences that do and should follow from breach of the concept,” (Professor Paul Craig, House of Lords Select Committee, Constitution Sixth Report, Appendix 5).

The oft heard assertion that the Claim of Right merely upholds the rule of law, (the principle of the legal limitation of even the highest authority in the nation), is a fudge in the context of an unlimited (sovereign) parliament wherein no meaningful mechanism for the enforcement of such limitation actually exists. (As many commentators have bemoaned and as we see all too clearly today.) And the fudge is simply a means by which to iron out ‘the Scottish constitutional anomaly’ with sophistry.

The Claim of Right establishes not the rule of law, but the Scottish constitutional compact, which is to say that it neither sets out to establish, nor does it establish, the rule of law. (A very large body of statutes and provisions exists to do that.) Rather, it establishes the *relationship* between the rule of law in Scotland and the precise and enforceable limits which that relationship imposes on a government, (crown in parliament). It is unique among the constitutional statutes of the UK in explicitly and unambiguously doing so.

It is not required to say, “And finally, if the wheels come off the foregoing arrangements, then we’ll all get together in a big meeting.” Any more than the Bill of Rights is required to say “And from now on the powers formerly vested in the monarch belong to the parliament.” Because what it explicitly does say is that, by violating the rule of law, (it also states which laws), James VII has forfeited the throne. It imposes a specific and final penalty.

This is something the English parliament dared not do and thus it used the less than honest device of pretending that James had abdicated. Perhaps I should add that the assertion in the English Bill of Rights that James had breached the limits of sovereignty imposed by parliament, (and, indeed, that sovereignty already resided in the parliament), would have astonished Henry VII who introduced the European doctrine of the divine right of kings, Henry VIII who ruled as an absolute monarch and Elizabeth who did much the same as well as the Stuart kings who fell head over heels for the idea on arrival in England.

The power of the monarch did not require to be limited or altered by the Claim of Right Act, as it did in England by the Bill of Rights. Rather the Claim of Right enforced the existing limits, setting the rule of law within its Scottishconstitutional context and giving it considerably more force and meaning in terms of accountability for government abuses and violations than now exists in the UK. (It continued to do so after 1689, preventing William of Orange from limiting the power to petition over the Darien scheme in 1699.)

For proper context, we should be aware that, at times, James VII used both parliament and the Court of Session to “cass annull and dissable all the lawes”.But it was his intervention in the appointments to parliament from the burghs which was his real overreach, overruling the existing democratic process in the hope of using his own appointees to obtain parliamentary approval for his Catholic emancipation plans:

“In addition to participating in parliaments, royal and ecclesiastical burghs sent commissioners to regular meetings of the convention of royal burghs, which decided on matters of shared economic and fiscal concern, and prepared the towns’ collective response to parliamentary proposals.” (Raffe, Alasdair, ‘James and the Royal Burghs’ Scotland in Revolution, 1685-1690 Edinburgh, 2018)

James’ attempt failed, in fact, even before 1689. But here you see a very different disposition of power from that in England. (Imagine, today, parliamentary proposals requiring a response from ‘the towns’?)

The interrelationships between the people, the burgh ‘councils’, burgh convention (or assembly) and parliament and between the Convention of the Estates and these bodies enabled the interchange of draft legislation, opinion and amendment in a way that simply did not and exist in England and does not exist in the UK today. And this brings me to the central problem underpinning the argument.

The author applies an English prism to a uniquely Scottish constitutional arrangement. This is a longstanding and almost universal error stemming from an internalised, colonising mentality and one that persists so that, where autochthonous interpretation is now extended to the constitutions of former colonies, no such courtesy is extended to Scotland.

The Convention of the Estates was ‘parliament-lite’ because it was usually called by the king? (Usually but not always.) But why, when it was often more heavily populated than the parliament and at least as difficult to control, (as the record of the parliaments of Scotland demonstrate), did the king choose to call a Convention when he could just as easily summon a parliament? Particularly when many of the same people attended the Convention as did the parliament?

The fact that a ‘parliament lite’, (the only available interpretation through an English prism), cannot satisfactorily explain why and how it existed, except as a kind of vestigial organ, like an appendix, continuing after its original function is lost, ought to be a red flag. It ought at least to raise the question, “Have I applied a foreign concept to a Scottish arrangement and come up with a deeply unsatisfactory and complicated characterisation as a result? Is there an Occam’s razor explanation that is far simpler and more elegant?”

As it happens, there *is* an Occam’s razor explanation. The Convention fulfilled a uniquely Scottish function. That function has never been examined in the light of its origins nor of the persistence into the 17th century of the influence of an indigenous legal and political tradition that had roots neither in Anglo-Norman feudalism nor Roman canon law. The ‘loan of power’ by the people to the government, monarch, monarch in parliament or chief is a widely recognised, early Scottish principle. (An early form of ‘devolution’ that was the reverse of the present, top down arrangement!) It was not a European idea imported by Bruce in 1320, though he used contemporary language to ‘update’ it, nor by Buchanan in the 1500s. And those whose power is loaned might well require some sort of insurance mechanism, in lieu of a medieval ‘Scotland Act’.

The most immediate effect of governmental power for the ordinary person on an ordinary day is the imposition of taxes. Thus no tax could be raised without the consent of the Convention of the Estates. Enough said. Nor could gifts from the treasury be made without its consent. It was the Convention that decided and negotiated the side taken by Scotland in the civil war and the treaty with the parliamentarians. It was the Convention (then General Council) that stepped in during the minorities of four Scottish monarchs. And, of course, it was the Convention that stepped in when no legitimate parliament could be called and acted on behalf of the nation in 1689.

So what was the real standing of the Convention of the Estates? What real power did it have compared to that of the parliament? How was it understood? In terms of its authoritative scope, perhaps the best exponent is the jurist who detested it claims and whose writing continues to provide the underpinning theory of Westminster constitutionalism, A. V. Dicey. He complained that the powers asserted by the Claim of Right Act are:

“In effect a demand for every power belonging to the Parliament of England … far exceeding any power which (the Scottish Parliament) actually possessed and exercised before the Revolution of 1689” (Dicey, A. and Rait, R., ‘Thoughts on the Union Between England Scotland’, London: Macmillan 1920

He was right in so far as no Scottish Parliament ever claimed such powers for itself. Through the Claim of Right Act, however, and on behalf of the nation of Scotland (which is to be understood through the documents and provisions of the uncodified Scottish constitution), the Convention of the Estates does. (It is also worth observing that, for the Imperialist jurist A. V. Dicey, one of the most obnoxious powers both claimed and exercised by the Convention of the Estates must surely have been that of declaring two rulings of the Court of Session unlawful. An interesting precedent?)

“If the wheels come off, we’ll all get together in a big meeting, which let’s at least agree now we’ll call a convention of estates”? That had *long* been understood and had been put into effect many times before the 1689 Convention of the Estates. And that is the point. What was once well understood in Scotland was and is alien to the English disposition of power. (But we shall yet beunderstood in the light of our own constitutional arrangements, development and historical record. Not those of a foreign power!)

There was, in Scotland, a much more complex disposition of power than that which in England was largely defined by the conflict between the sovereignty of the parliament and the monarch. And it is the very character of that widely dispersed authority and influence, monarch, privy council, Lords of the Articles, Parliament, Convention, Burgh Assembly burgh councils and more, which encapsulates the sovereignty of the people. The sovereignty that is claimed for the nation is claimed for *all* the people, high and low as defined in another constitutional document, the Declaration of the Clergy of 1310, once again in the Declaration of Arbroath and then by the Claim of Right Act 1689.

Finally, I have a confession. Much as I have enjoyed writing this, because it isalways a pleasure to set the record straight and a duty to break the hold of dogma, none of this is necessary.

Whatever its status prior to the assembly at which the Claim of Right was passed, what matters is the status the Act assigns to the Convention that passed it – that of “a free and fair representative of the nation”. (The nation as defined in previous constitutional *Scottish* documents.)

What matters is not whether the Convention had the powers it claimed, powers so profound that the claim scandalised Dicey, but that its self-proclaimed authority was upheld in 1689 when its members replaced the parliament of James VII (deposed with the crown), and in 1703 when it was enacted by that parliament:

“that it shall be high treason for any person to disown, quarrel or impugn the dignity and authority of the said parliament… “

And

“that it shall be high treason in any of the subjects of this kingdom to quarrel, impugn or endeavour by writing, malicious and advised speaking, or other open act or deed, to alter or innovate the Claim of Right or any article thereof.”

What matters is that, as a constitutional document, protected in Scotland under penalty of high treason, made a condition of the Treaty and ratified with the Acts of Union as a condition of Union, recognised post Union by the parliament at Westminster, the Claim of Right confers upon the authorising body, the Convention of the Estates the status *it assigns to itself* with the force of constitutional law. Exactly as the Bill of Rights constitutes the principle ofsovereignty in the English parliament. The Claim of Right states that the Convention of the Estates is a free and fair representative of the nation, (as defined in previous constitutional *Scottish* documents) and, therefore, such is its status. The Convention, not the parliament. Not the crown in parliament.

Most of all, what matters is that this is a constitutional argument about the basis for fundamental constitutional change. And constitutional change is, as we know, effected as much, possibly much more, by political will and action than by legal action.

What *will* matter is whether the majority of Scots choose to interpret their rights and their sovereignty in the terms which I, and many others before me, have asserted and to exercise their democratic right to act accordingly. If they do, it will matter very little whether any legal opinion or court ruling says otherwise. Because ultimately, whatever existing legal interpretation might say to the contrary, history tells us that when it is not vested in the weapons of war, power is always vested in the people.

As for the practice of Salvo and whether it demonstrated the sovereignty of the people over their government, I will leave the last word to the late naval captain, lawyer and orator as well as assiduous researcher of Scots law and history, Willie MacRae. Along with a promise that I will find, as he clearly did, the records of this practice, not in the statutes but as offered in the way that he describes:

“After the Act of Union was passed on the 16th of January 1707 there was one further item of business, as there was at the end of every session of the Scottish parliament and that was the Act of Salvo (salve jure cujuslibet – let whosoever sue the Crown). This was a gesture respectful of the Scottish constitutional arrangement whereby the People are sovereign and every subject of the kingdom must be respected both as an integral and individual unit of sovereignty, much like any part being representative of the whole of a hologram. Every subject was thus left with the means of escape, the private right to contract out if they felt they had been wronged by the action of the Crown. The English parliament, in 1689 having reduced its subjects to citizens behoven to the sovereign court of Westminster gave no such opportunities for redress and still does not, but the parliament in England cannot claim now to have inherited powers over the subjects of Scotland that the Scottish Parliament did not have.”

MY COMMENTS

I am grateful to both Neil and Sara. They have demonstrated that it is perfectly possible to debate these matters in a polite and professional manner, neither Party calling the other names but seeking to promote their positions with respect to the other Party. How rare is that in politics these days.? I am sure this is just the start of a really good debate on these topics.This is precisely what I hoped for this blog. We all learn more when we are aware of our opponents arguments as well as our own and accepting the challenge of defending our pro Indy positions in advance is a very worthwhile exercise for the challenges ahead. I know Mia will also want to respond so that is something to look forward to in the near future.

I am, as always

YOURS FOR SCOTLAND

BEAT THE CENSORS

The purpose of this blog is to advance Scottish Independence. That requires honesty and fair reporting of events and opinions. Some pro SNP Indy sites have difficulty with that and seek to ban any blogger who dares to criticise the Party or its leader. As Yours for Scotland will not bend our principles and allow this attack on free speech to be successful we rely on our readership sharing and promoting our articles on a regular basis. This invalidates the attempts at censorship and ensures the truth gets out there. I thank you most sincerely for this important support.

FREE SUBSCRIPTIONS

Are available from the Home and Blog pages of this website. This ensures you are advised of every new article published on Yours for Scotland. Join the thousands already subscribed and be the first to get the news every day. You will be most welcome.

SALVO

This site has never sought donations, indeed we have a £3 limit alongside a message further explaining that donations are not required. That has now changed as the costs of running this blog for 2022 have already been raised in donation, therefore for the remainder of this year all donations made to this site will be forwarded to Salvo to help them educate Scots on the 1689 Claim of Right. This is vital work and we must all do what we can to support it.

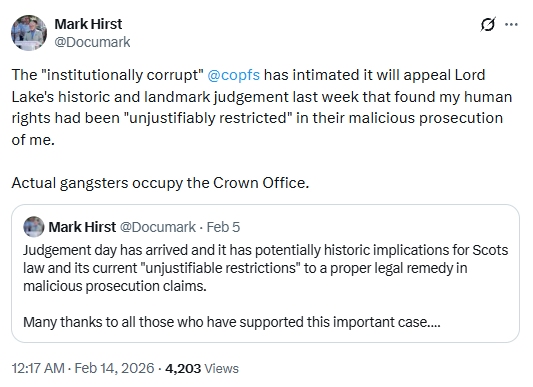

What's Your Reaction?