THE CHALLENGE HAS BEEN ACCEPTED. A CHAMPION FOR THE UNION HAS BEEN FOUND!

THE CHALLENGE HAS BEEN ACCEPTED Last week I challenged opponents of Independence to set out their argument why the Claim of Right 1689 was not the game changer many in Scotland believe it is. I offered anyone the opportunity to have their article published setting out the reasons they held this view. I have doneContinue reading "THE CHALLENGE HAS BEEN ACCEPTED. A CHAMPION FOR THE UNION HAS BEEN FOUND!"

THE CHALLENGE HAS BEEN ACCEPTED

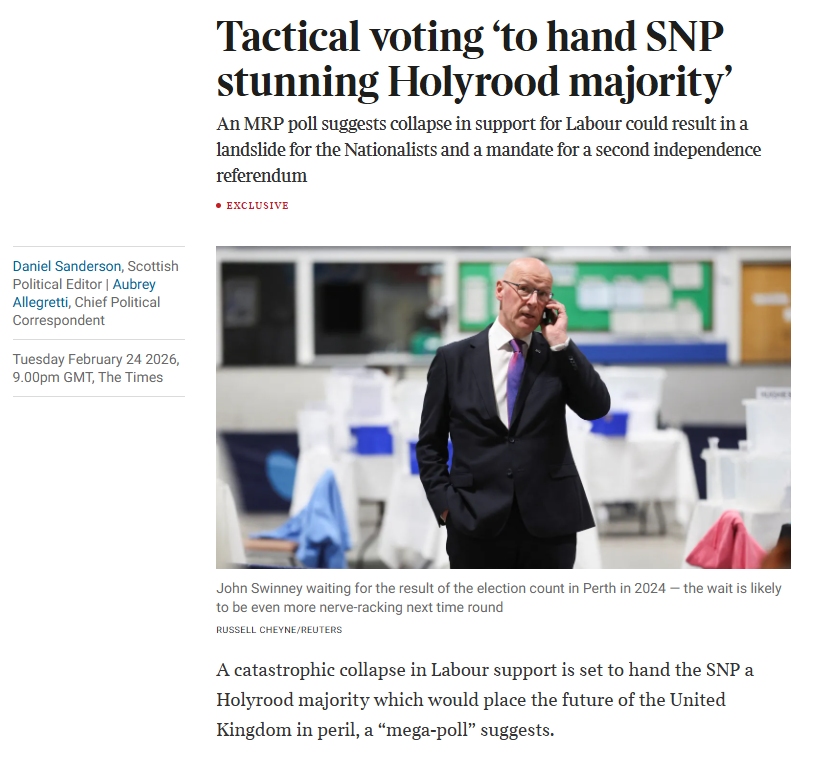

Last week I challenged opponents of Independence to set out their argument why the Claim of Right 1689 was not the game changer many in Scotland believe it is. I offered anyone the opportunity to have their article published setting out the reasons they held this view. I have done this before, but unlike previous attempts to tease out counter arguments, a retired lawyer Neil King has set out his argument below. Neil does not support Independence but tells me he wrote this article as a retired lawyer rather than just being a Unionist. His article is being published here without alteration. I think we can all learn and benefit from hearing alternative views and I am positive this article will generate quality debate which is exactly what this blog sets out to achieve. So thank you Neil for playing your part in this. Neil lives in Portugal but did practice law in Scotland before retirement. Later today Yours for Scotland will publish a reply to Neil from Sara Salyers of Salvo.

The Claim of Right 1689 and popular sovereignty

Sovereignty

The sovereignty of parliament (or parliamentary sovereignty for short) is the principle of the British constitution that the highest authority in the land is parliament (I mean the Westminster Parliament here).

The easiest way to explain that is to contrast the UK with most other countries where the highest authority is not the legislature but the country’s constitution. What that means is that an act of parliament can be challenged in the courtsand struck down if it violates the country’s constitution. Although it’s not a term of art used by constitutional lawyers, I’m going to call this constitutional sovereignty to distinguish it from parliamentary sovereignty. Perhaps the most famous example of it in action is the American case of Roe v Wade. Ms. Roe wanted an abortion but a Texan statute prevented that. She challenged the statute and the US Supreme Court eventually struck it down because it violated her constitutional right to personal liberty and privacy: the US Constitution trumps the Texan legislature. In Britain, there’s no equivalent of this. If the WestminsterParliament passed an Act banning abortion, it couldn’t be challenged in court. That’s because parliament is sovereign.

Turning to the Claim of Right 1689 (CoR) – and the first thing I’d urge anyone commenting on the CoR to do is read it! You can do that here – the claim is that it enactedthat, in Scotland, sovereignty lies not with parliament (or a constitution) but with the people. In contrast toparliamentary and constitutional sovereignty, this is called popular sovereignty. So, if parliament passes an Act which somebody doesn’t like, appeal may be had to the people at large. This – the argument continues – was different from the position in England before the Union where parliament was sovereign but the CoR was specifically preserved in the Acts of Union and continues in force in Scotland. If that is so, then, if the Supreme Court rules that the correct interpretation of the Scotland Act 1998 is that it prevents the Scottish Parliament from enacting a new indyref, then appeal may be had to the people of Scotland.

Did the CoR enact popular sovereignty?

No. The proponents of popular sovereignty based on the CoR have – with respect – mixed up the question of the location of internal sovereignty (parliamentary, constitutional or popular) with another cardinal principle of most constitutions (including the UK’s), the rule of law.

That is the concept that the executive (today, the government, in previous centuries, the king) cannot do as it pleases: it has to comply with the law just like everybody else. (As we’ve now introduced two fundamental principles of most constitutions – internal sovereignty and the rule of law – it’s worth mentioning here the third: the separation of powers between parliament (which makes the law, subject in many countries to limitations in the constitution), the executive (which administers the law made by parliament) and the judiciary (which decides what the law is when in doubt). That’s not too much of a digression because it really helps when trying to understand these things to keep all three in mind: even when concentrating on one of them, the other two are never far away.)

Anyway, the significance of the CoR is not that it enacted popular sovereignty, it’s that it enacted the rule of law. Well, it didn’t so much enact it (there’s no sentence in the CoR – I urge you again to read it – saying “From this day forth, the rule of law shall apply in the kingdom of Scotland …”) it more articulates that the rule of lawalready existed. Remember that the background was that King James VII had been acting like he owned the place, blithely ignoring various laws in pursuit of his religious policies and, when anyone challenged him, his response had, in effect, been “Hey, I’m the king appointed by God! The law doesn’t apply to me, I can do what I like!” That’s what the CoR declared was not on. You can see this in the following wording in the CoR (which its proponentswrongly point to as evidence of popular sovereignty) that James did:-

invade the fundamentall constitution of this kingdomeand altered it from a legall limited monarchy, to anearbitrary despotick power; and in a publickproclamation asserted ane absolute power, to cass, annull and dissable all the lawes, particularly arraigning the lawes establishing the Protestant religion, and did exerce that power to the subversion of the Protestant religion, and to the violation of the lawes and liberties of the kingdome

Convention of Estates

When challenged on the significance of the CoR, proponents of popular sovereignty sometimes seem to change tack a bit and say it’s not the CoR itself that’s important, it’s the body that passed it. That, the argument runs is because that body wasn’t a parliament it was a higher, more authoritative assembly of the people at large called a “convention of estates”, a regular feature of the pre-Union Scottish constitution.

It’s true that, although it looked very like one bar some abstruse technicalities about the franchise in burghs and the oaths to be sworn by its members, the body that passed the CoR wasn’t, strictly speaking, a parliament. That’s because it hadn’t been summoned by the king (James VII) but by William of Orange (who’d not yet been proclaimedking) at the invitation of a group of powerful Scottish noblemen. But it met in the middle of a revolution (the overthrow of James VII) and revolutionary proceedings are in their very nature unconstitutional. So to suggest that this ad hoc meeting in extraordinary circumstances was a regular feature of the Scottish constitution is not correct –unless you imagine that constitution to have had a clause at the end of it (and I’m joking here because pre-union Scotland didn’t have a written constitution either) saying something like “And finally, if the wheels come off the foregoing arrangements, then we’ll all get together in a big meeting, which let’s at least agree now we’ll call a convention of estates, and hopefully sort something out.”

It’s also true that conventions of estates were a feature of the Scottish constitution. But they weren’t some supreme body that emerged from time to time to restrain parliament in the name of popular sovereignty. Quite the contrary, conventions were, if anything, subservient to parliament.The precise distinction between a convention (previously known as general councils) and a parliament is a highlyesoteric subject you can read about here (long and boring) or here (two short paragraphs: bottom of page 18 and top of page 19). Suffice to say, conventions were a sort of parliament-lite that could transact most but not all the business an actual parliament could with slightly less formality. They also had to be summoned by the king (so the body that enacted the CoR in 1689 wasn’t a convention either, strictly speaking, although it’s often referred to as such).

Acts salvo jure cujuslibet

Proponents also point to a series of acts of the old Scottish parliament called the acts salvo jure cujuslibet (Latin for “reserving everybody’s rights”) as evidence of popular sovereignty. These acts, they claim, gave people the right to challenge acts of parliament.

Well they did but not all acts of parliament. Acts salvoonly applied to “particular acts” (those in favour of particular individuals such as remissions (pardons) for offences committed in the course of being politically useful to the crown – massacring Covenanters, that kind of stuff) and acts ratifying royal charters of lands or offices.The issue with particular acts and ratifications was that the crown granted them for its own interest but didn’t enquire into whether they might cut across the rights of third parties (such as a civil case arising out of a remitted offence or a prior claim on land granted by royal charter).Therefore, parliament passed an act salvo to make it clear that particular acts and ratifications were not intended to cut off any third party claims which would remain live to be decided in court. You can read an example of an act salvo here.

But acts salvo didn’t confer a right to challenge any act ofparliament and, properly understood, they’re not evidence of popular sovereignty. In fact they’re quite the opposite, they’re evidence of parliamentary sovereignty. That’s because, in passing them, parliament was saying to itself “Hang on a minute, we’re sovereign! Unlike the king, we can do what we like! If we’re not careful, we could be cutting off people’s rights. So we’ll need to pass an act saying that, in the case of particular acts and ratifications only, that’s not what we’re meaning to do.” (Note that the act salvo linked to above contains an exception for the Duke of Buccleuch’s marriage contract. That’s parliamentsaying “But we really mean it with that one. By the application of our sovereignty, we’re legislating away any potential third party claims against it.”)

Lord Cooper’s obiter dictum

Proponents of popular sovereignty also point to the following obiter dictum (remark by a judge in a judgementwhich is not necessary to the decision of the case in hand)by the Lord President of the Court of Session in the 1953 case of MacCormick v Lord Advocate:-

The principle of the unlimited sovereignty of Parliament is a distinctively English principle which has no counterpart in Scottish constitutional law.

Apart from being obiter (and thus not legally binding), the problem with this for proponents of popular sovereignty is that Lord Cooper didn’t go on to say where he believedsovereignty in Scotland did lie. It’s entirely possible he believed it was constitutional rather than popular sovereignty that applied in Scotland. There’s support for that in the fact that he appears later in his judgement (read it here) to approve of a passage by the celebrated writer onthe constitution A V Dicey which spoke of an “absolutely sovereign Legislature [i.e. Westminster] which should yet be bound by unalterable laws.” There’s even some support for it in the CoR – “the fundamentall constitution of this kingdome” it refers to the king having invaded. (These “unalterable laws” and “fundamental constitution” needn’t be contained in a written constitution in the sense of a single document like the USA’s.)

In summary, then, the CoR declared the rule of law, not popular sovereignty; there’s no evidence for constitutional popular sovereignty in the body that passed the CoR or other regular conventions of estates; nor is there in acts salvo jure cujuslibet which, if anything, evidence parliamentary sovereignty; and Lord Cooper’s dictum is neutral at best.

MY COMMENTS

I am going to leave it to others, better qualified than myself to reply to Neil’s article. I can hear the keyboards being pounded as I write. One plea, Neil has written his article politely and I hope the many responses I expect to be posted will also share that respect for the author. We should destroy the content with reasoned argument, not the author. I gave Sara Salyers of Salvo sight of this article in advance in order for her to prepare her reply. It will be published in a matter of hours on Yours for Scotland.

I am, as always

YOURS FOR SCOTLAND.

BEAT THE CENSORS

The purpose of this blog is to advance Scottish Independence. That requires honesty and fair reporting of events and opinions. Some pro SNP Indy sites have difficulty with that and seek to ban any blogger who dares to criticise the Party or its leader. As Yours for Scotland will not bend our principles and allow this attack on free speech to be successful we rely on our readership sharing and promoting our articles on a regular basis. This invalidates the attempts at censorship and ensures the truth gets out there. I thank you most sincerely for this important support.

FREE SUBSCRIPTIONS

Are available from the Home and Blog pages of this website. This ensures you are advised of every new article published on Yours for Scotland. Join the thousands already subscribed and be the first to get the news every day. You will be most welcome.

SALVO

This site has never sought donations, indeed we have a £3 limit alongside a message further explaining that donations are not required. That has now changed as the costs of running this blog for 2022 have already been raised in donation, therefore for the remainder of this year all donations made to this site will be forwarded to Salvo to help them educate Scots on the 1689 Claim of Right. This is vital work and we must all do what we can to support it.

What's Your Reaction?