SCOTLAND’S CLAIM OF RIGHT PART 1

PART ONE OF THE SERIES. THE FOREWORD IS BY PROFESSOR ALF BAIRD AND THE INTRODUCTION FROM SARA SALYERS TO THE PAPER IS PUBLISHED TODAY. EVERY DAY THIS WEEK THE FULL ARGUMENT AND EVIDENCE WILL FOLLOW. Foreword by Professor Alf Baird Scots are all too often left uncertain and confused when considering the critical matter ofContinue reading "SCOTLAND’S CLAIM OF RIGHT PART 1"

PART ONE OF THE SERIES. THE FOREWORD IS BY PROFESSOR ALF BAIRD AND THE INTRODUCTION FROM SARA SALYERS TO THE PAPER IS PUBLISHED TODAY. EVERY DAY THIS WEEK THE FULL ARGUMENT AND EVIDENCE WILL FOLLOW.

Foreword by Professor Alf Baird

Scots are all too often left uncertain and confused when considering the critical matter of their sovereignty, and intentionally so; for any colonial power will naturally seek to diminish the notion of native or national sovereignty that would inevitably interfere with a territory’s ongoing economic plunder and exploitation.

Ignorance of Scotland’s constitutional reality really hits the high notes when we get to the Claim of Right. The Claim of Right represents Scotland’s forgotten constitution, intentionally pushed out of sight and out of mind and hence denied us by our colonial oppressor, the latter including Scotland’s elites; colonialism, as Frantz Fanon reminds us, is always a cooperative venture.

The imposed sovereignty of a Westminster Parliament on Scotland’s people does not and never has corresponded with Scotland’s constitutional rights, namely, the rights conferred by the sovereignty of the people. In this is evident the distinct, cultural uniqueness of Scotland’s constitutional reality amidst the imposition of an alien English constitutional principle, the latter unlawful and in clear violation of the Treaty of Union itself.

This is because, as Sara Salyers explains, the Treaty itself is conditional on Scotland retaining its own distinctive constitution, contained and described in the Claim of Right Act of 1689. This condition means that the Scottish people retain the right to prohibit government actions or legislation which compromise their civil rights and freedoms. This is part of the ‘right’ referred to in the Claim of Right and enshrined in Scots law by the Act ‘salve jure cujuslibet’ of 1663, which allowed any Scot to challenge parliamentary legislation which infringed their civil liberties – and how refreshing is that kind of thinking even today, never mind the seventeenth century. And still necessary too, even in our supposedly more democratic times, when governments aye have a tendency to take forward legislation which all too often is intended to oppress the people rather than serve them, as Nelson Mandela once said.

It means, above all, that the Scots retain the right, even today, to remove a governing authority when it no longer functions in the interest of the Scottish people, this being the main purpose of the Convention of the Estates (the assemblies of the communities).

The ability to depose a monarch and/or remove an unwanted government remains arguably the central basis and purpose of the Claim of Right, vesting sovereignty firmly in the hands of the Scottish people themselves, rather than any shower of mankit elites in Westminster or Holyrood. Hence, constitutionally, it is the Claim of Right whit maks us Scots unalik maist ither naitions! Our constitutional reality is therefore diametrically opposed to the English doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, the latter underpinning England’s constitution, but never Scotland’s.

The Scottish Claim of Right was never extinguished by the Treaty of Union; rather, the treaty was and remains conditional upon the continuance of the Claim of Right in Scotland. Westminster, which is not a party to the Treaty of Union but merely an outcome of it, cannot itself alter the original conditions of the treaty, this may only be done through agreement of the respective signatory parties – Scotland and England.

Rather than a case of England’s parliament subsuming Scotland, the treaty established and states as such that a new parliament was created as the First Parliament of Great Britain. Westminster is and remains a joint legislature and governing administration established by treaty and is therefore a consequence of a treaty-based alliance between two sovereign nations, each still holding and retaining separate and distinctive constitutions. In other words, the two sovereign signatory party nations to the Treaty of Union continue to exist, as does the continuation of their quite different constitutions, the respect of which remains a condition of that agreement, failing which there can be no ‘union’.

The real problem here is that Westminster has and continues to pay lip service to the reality of Scottish sovereignty, while treating Scotland as subject to England’s constitutional parliamentary sovereignty, and hence dismissing Scotland as a distinct sovereign entity with its own constitutional rights. England, and it has to be said also the Scottish elites, has disregarded the Claim of Right as enshrined in the treaty and ignores the fact that ultimate power in Scotland rests with the sovereign Scottish people, a power which they have the right to exercise through the Convention of the Estates as the assembly of all the communities of Scotland.

Scotland’s list of grievances are many, as reflected in numerous violations to the Treaty of Union, an enforced Brexit merely being the latest in a long list. Moreover, the electorate’s instructions conveyed to Scotland’s politicians in favour of independence, repeatedly given by the people, have been disrespected by the SNP at both Westminster and Holyrood, which under the Claim of Right serves as further violation of the peoples’ liberty and possible grounds for forfeiture of the right to govern.

As Sara Salyers explains in this excellent analysis of Scotland’s Claim of Right, the Convention of the Estates must now be re-convened as what it is – the representation and assertion of ultimate, sovereign power of the people of Scotland – its principle function being to prevent Scotland from being subject to ony arbitrary despotick pouer, or to unjust laws, and to withdraw Scotland from this mankit Treaty of Union or any other treaty that may no longer be in Scotland’s interest.

Professor Alf Baird

The Laws of Government, (in Scotland), continue as the Government continues establish’d in the Claim of Right, I mean as to the Limitations of Government and Obedience (Daniel Defoe)

Introduction

In 2016, the High Court in England heard an appeal against the government’s decision to trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union without consulting parliament. In its ruling, (which went against the government), the High Court took pains to assert that the authority of parliament is supreme in all parts of the UK and to state explicitly that it has no need to take account of the wishes of the people:

(b) The sovereignty of the United Kingdom Parliament

20. It is common ground that the most fundamental rule of UK constitutional law is that the Crown in Parliament is sovereign and that legislation enacted by the Crown with the consent of both Houses of Parliament is supreme (we will use the familiar shorthand and refer simply to Parliament). Parliament can, by enactment of primary legislation, change the law of the land in any way it chooses. There is no superior form of law than primary legislation, save only where Parliament has itself made provision to allow that to happen. The ECA 1972, which confers precedence on EU law, is the sole example of this.

21. But even then Parliament remains sovereign and supreme, and has continuing power to remove the authority given to other law by earlier primary legislation. Put shortly, Parliament has power to repeal the ECA 1972 if it wishes.

22. In what is still the leading account, An Introduction to the Law of the Constitution by the constitutional jurist Professor A.V. Dicey, he explains that the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty means that Parliament has: “the right to make or unmake any law whatever; and further, that no person or body is recognised by the law … as having a right to override or set aside the legislation of Parliament.” (p. 38 of the 8th edition, 1915, the last edition by Dicey himself; and see chapter 1 generally). Amongst other things, this has the corollary that it cannot be said that a law is invalid as being opposed to the opinion of the electorate, since as a matter of law:

”‘The judges know nothing about any will of the people except in so far as that will is expressed by an Act of Parliament, and would never suffer the validity of a statute to be questioned on the ground of its having been passed or being kept alive in opposition to the wishes of the electors.” (ibid. pp. 57 and 72).

The importance of parliamentary sovereignty is that it defines the relationship between the people and the government in the U.K.

At present, Parliament is recognised as being sovereign over the people, with the power of an absolute monarch, and, at the same time, the elected representative of those same people, all their rights and all their interests. As a result, all our civil rights and obligations exist at the discretion of parliament.

The only mechanisms by which the people are allowed to influence the policy and decision making of parliament or the government are voting in elections or by petitioning the government. Neither one is guaranteed to produce a result that reflects the will of the people, even of the vast majority of the people. This, however, is what we have accepted as a democratic system, one in which the rights and responsibilities of every man and woman are vested in a handful of politicians with no legal obligation to represent our real wishes or interests.

This is what the High Court ruling of 2016 reaffirmed. But because something has been ruled on, even by the highest Courts in the land, does not always make it true or lawful. In the first place, no court has authority to make, remake or ignore constitutional law. In the second, the arguments supporting the legitimacy of parliamentary sovereignty in Scotland do not stand up to scrutiny.

And, there is a Scottish constitution, though it is ignored by this ruling and many others. It iswritten, though it has been forgotten or denied. It may be basic and undeveloped but it isrobust. And it was ratified along with the Articles of Union, as a condition of both the Treaty of Union and the Union itself. It is set out in the Claim of Right Act of 1689. We know it as popular sovereignty.

In direct opposition to the English doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, sovereignty in Scotland is reserved to the people of the nation. Popular sovereignty constrains the powers of government and makes the government answerable to the people, to the extent that any statute or policy is open to national challenge and rejection. As is any government that oversteps its bounds. At least, that was the case until the Treaty of Union and it was certainly intended to continue to apply in Scotland after the Union, as we shall see.

The passage of time and the acceptance of the customs of English constitutional law as universal norms across the UK, make this description of Scotland’s constitutional law seem like a romantic interpretation, more wishful thinking than fact. In reality, however, it is the status of parliamentary sovereignty in Scotland that is wishful thinking. As Lord Cooper famously ruled:

“the principle of the unlimited sovereignty of Parliament is a distinctively English principle which has no counterpart in Scottish Constitutional Law”

Not only has it no counterpart, it might be more exact to say that the constitutional right of the Scottish people to override parliamentary legislation or set aside the government itself, has no counterpart in English Constitutional Law. In fact, under the Claim of Right, the very assertion that Westminster has absolute sovereignty over the people of Scotland is an explicit violation of “the fundamental constitution of Scotland”. Which makes the High Court ruling not merely erroneous but unlawful.

It also means that the Diceyan argument, cited in the High Court ruling, with its focus on the relationship of the Treaty to the Acts of ratification, (or Acts of Union), and of the Acts to the UK Parliament, is secondary to a more fundamental relationship; the relationship of the Union itself to the conditions that were imposed, agreed on and ratified. (For this reason, the second objection to the High Court Ruling, its interpretation of constitutional power in the United Kingdom according to the arguments of A. V. Dicey, is addressed in the appendix.)

The force of the ratified Scottish constitution cannot lawfully be replaced by the force of the English Constitution simply because Westminster wishes it so, which is why Lord Cooper ruled as he did. And rewriting or recasting the terms, context and meaning of the Treaty of Union are not among the ‘sovereign’ powers of Westminster. The UK government is – and long has been – in breach of a permanently binding and still ‘live’ condition of the Union. It is past time to rectify that breach and to return to the rule of law instead of a version of law that is simply establishment wishful thinking.

The people of Scotland have the right to demand the return of their sovereignty over the government, both in Westminster and Holyrood. This includes the right to challenge and strike down laws and statutes that violate “the lawes and liberties of the Kingdome”, (especially human and civil rights), and the right to declare a government “forfeit” which has abrogated the sovereignty of the people and assumed an absolute authority to “case anull and disable” the laws that exist for the protection of the freedoms, lives and wellbeing of the people.

It is time to end the indignity of being ignored in our millions, as we go cap in hand for justice and humanity to those who use a power that is only loaned to them against those from whom they have borrowed it. There is more at stake here than independence from Westminster and the establishment of a sovereign, Scottish state. Arguably, the most pressing struggle of our time is not the struggle of a small nation against the domination of a larger one but the struggle for human and environmental rights and interests against the power and vested interests of a controlling and unaccountable elite. Any hope of replacing the present, broken power structures in Scotland depends on independence. But it has never mattered more what kind Scotland we could create, independent or not.

Scotland’s forgotten constitution can offer a pathway to freedom from Westminster rule. But it might contribute something even more important in terms of global change. It might help to propel a wider shift in the balance of power, away from the obscenely disproportionate control of an unaccountable minority and towards the legitimate authority of the people. And by reclaiming its own constitution, Scotland has the potential to blaze a trail for the kind of democracy that the world now urgently needs.

BEAT THE CENSORS

Sadly some sites had given up on being pro Indy sites and have decided to become merely pro SNP sites where any criticism of the Party Leader or opposition to the latest policy extremes, results in censorship being applied. This, in the rather over optimistic belief that this will suppress public discussion on such topics. My regular readers have expertly worked out that by regularly sharing articles on this site defeats that censorship and makes it all rather pointless. I really do appreciate such support and free speech in Scotland is remaining unaffected by their juvenile censorship. Indeed it is has become a symptom of weakness and guilt. Quite encouraging really.

FREE SUBSCRIPTIONS

Are available easily by clicking on the links in the Home and Blog sections of this website. by doing so you will be joining thousands of other readers who enjoy being notified by email when new articles are published. You will be most welcome.

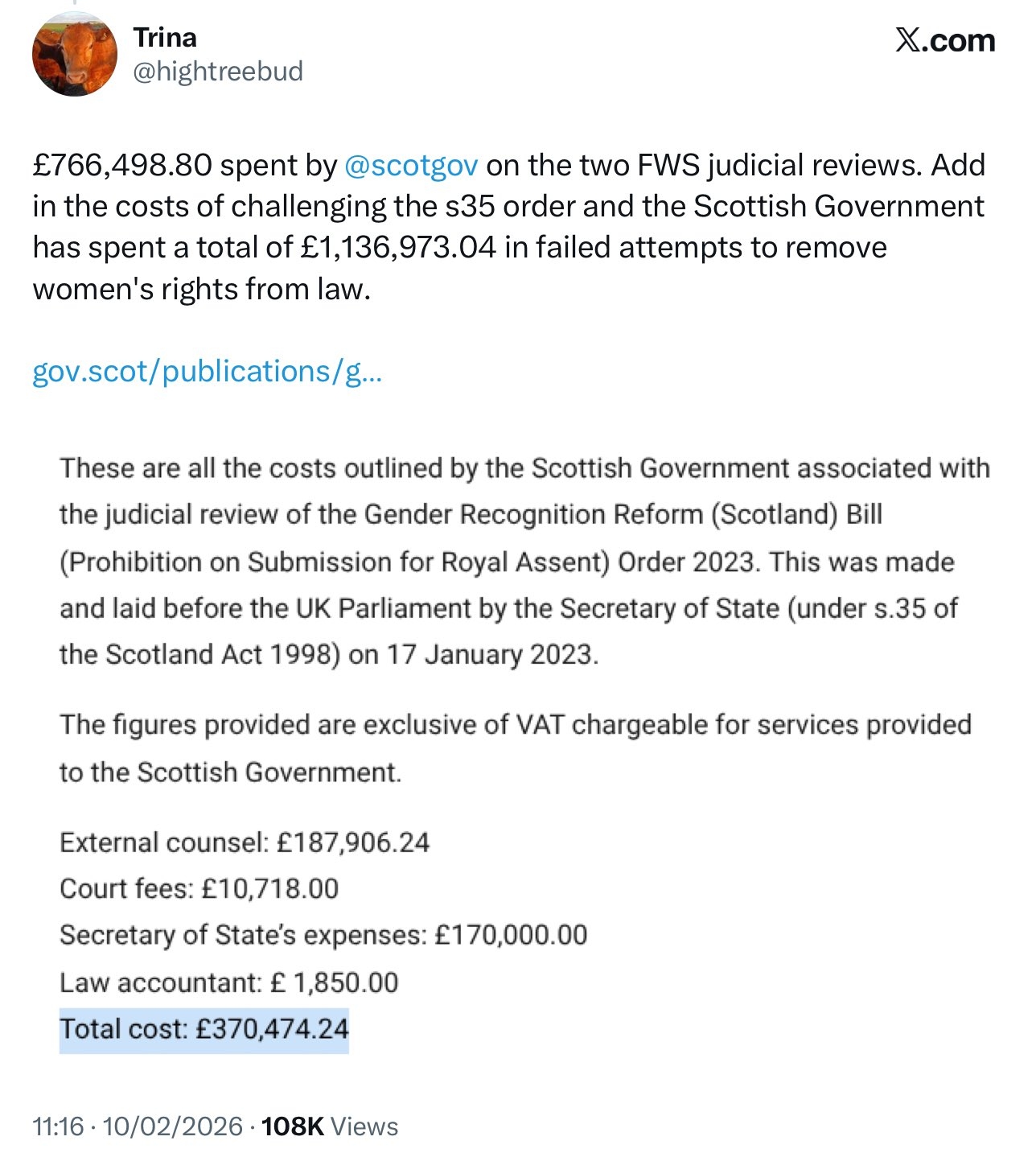

What's Your Reaction?