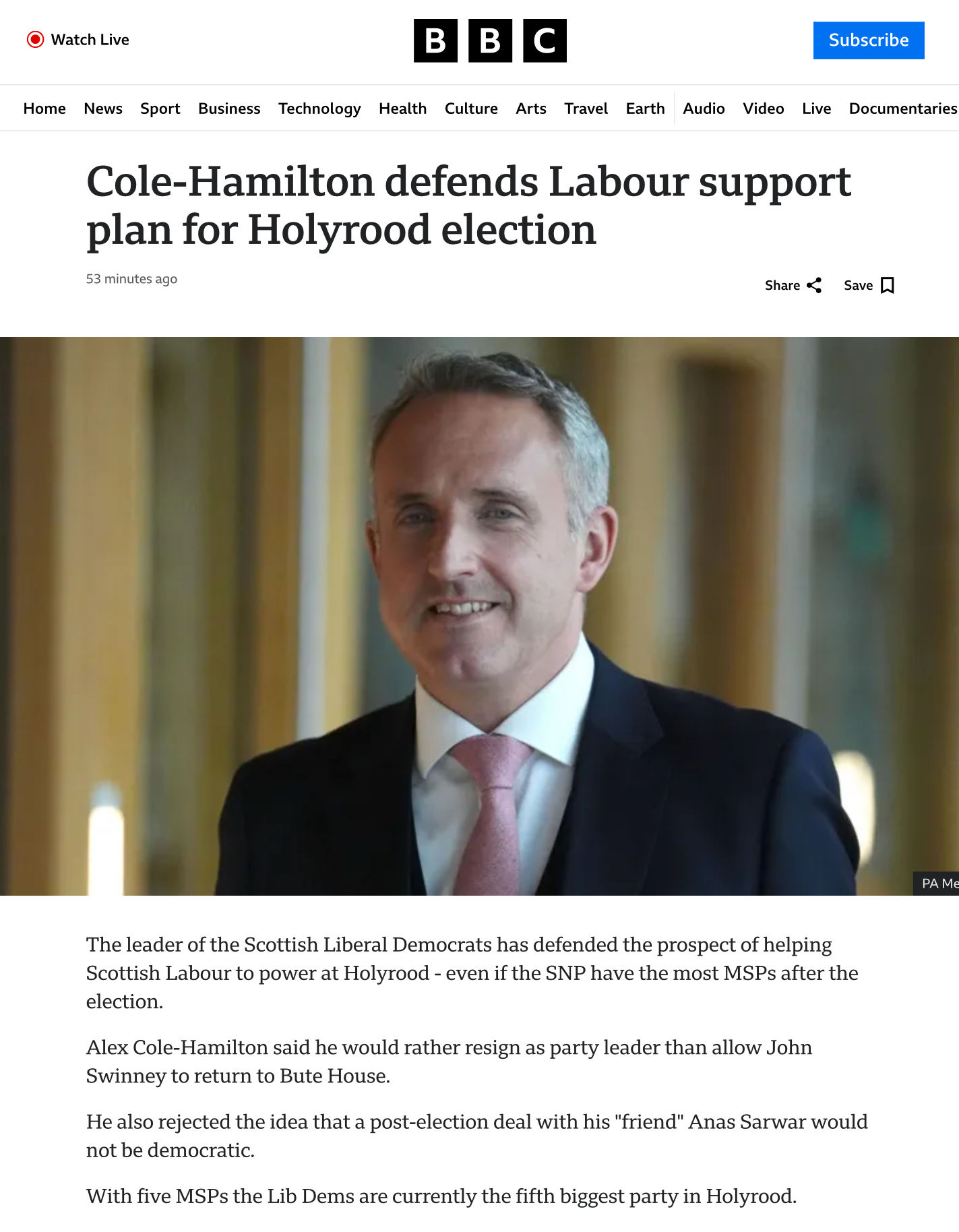

SCOTLAND’S CLAIM OF RIGHT PART 5

Appendix Demolishing Dicey: the strange case of the treaty that wasn’t In 1689, the English Parliament enacted its Bill of Rights. This was the same year in which that other, central, UK constitutional document, the Claim of Right was passed in Scotland. The force and intent behind the two Acts were the same, the removalContinue reading "SCOTLAND’S CLAIM OF RIGHT PART 5"

Appendix

Demolishing Dicey: the strange case of the treaty that wasn’t

In 1689, the English Parliament enacted its Bill of Rights. This was the same year in which that other, central, UK constitutional document, the Claim of Right was passed in Scotland.

The force and intent behind the two Acts were the same, the removal of the Catholic monarch (King James VII) and his replacement with an acceptable alternative, William of Orange. The ways in which these two Acts codified the power of government, however, were diametrically opposed.

The Bill of Rights replaced the absolutism of the monarchy with the absolutism of the English Parliament in what is known as the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty.

The rule of law also requires the government to exercise its authority under the law. This requirement is sometimes explained with the phrase “no one is above the law.” During the seventeenth century, however, the English monarch was vested with absolute sovereignty, including the prerogative to disregard laws passed by the House of Commons and ignore rulings made by the House of Lords. In the eighteenth century, absolute sovereignty was transferred from the British monarchy to Parliament, an event that was not lost on the colonists who precipitated the American Revolution and created the U.S. Constitution

Since the constitutional settlement brought about by the Bill of Rights, 1689, the UK Parliament has had unchallenged authority to create primary law. Parliament’s legislative supremacy means, therefore, that there is no competing body with equal or greater law-making power and there are no legal limits on Parliament’s legislative competence.

In England, Parliament has supreme authority in every jurisdiction, including the rights of the individual. Any of those rights which we might assume to be somehow constitutionally or legally protected, (individual or collective, from tenants’ rights and workers’ rights to basic human rights), exist at the will and favour of the UK Parliament. But in Scotland, such absolutism is specifically rejected as unlawful and ‘despotyck’ by the contemporary Claim of Right. James VII and II was deposed on the grounds that he:

“Did By the advyce of wicked and evill Counsellers Invade the fundamentall Constitution of this Kingdome And altered it from a legall limited monarchy to ane Arbitrary Despotick power.”

This is the clearest possible statement of the principle that, in Scotland, an unaccountable, absolute (“despotyck”) government is contrary to “the fundamentall Constitution of this Kingdome”.

To this day, the English Bill of Rights and the Scottish Claim of Right remain incompatible. Both Acts, however, were passed eighteen years before the Treaty of Union was ratified and so neither Act had any effect on the other’s government. Sovereignty has been represented, nonetheless, as the central character of the UK Parliament.

As expressed by Victorian lawyer A.V. Dicey, whose ‘The Law of the Constitution’ “has been the main doctrinal influence upon English constitutional thought since the late-nineteenth century”, it remains the underpinning legal authority for even Supreme Court judges.

The principle of Parliamentary sovereignty means neither more nor less than this, namely, that Parliament . . . has, under the English constitution, the right to make or unmake any law whatever; and, further, that no person or body is recognised by the law of England as having a right to override or set aside the legislation of Parliament.

the sovereignty of Parliament is (from a legal point of view) the dominant characteristic of our political institutions.” (It is) … “is no less than “the central principle” of the system, “on which all the rest depends”

It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of the claim that Westminster’s sovereignty lawfully extends into Scotland. If Westminster is sovereign in Scotland, it can remove or alter any Scottish legislation at will. It has already done so. Rights to protest, to expect safe and decent working conditions, to demand and get decent wages, to expect that taxes should be collected fairly and without special ‘arrangements’ for the few, to demand safe, healthy and sustainable industrial and environmental practices and much, much more are non-existent. They may be granted or removed at will. And it is for Westminster to determine any alteration in the terms of the Union. If Westminster is sovereign in Scotland, the sovereign nation of Scotland is not sovereign at all.

Given the status of the Claim of Right, however, the absolutism of Westminster can only apply in Scotland if something extinguished it in Scotland, along with the Parliament. But if so, what and how did it do so? What legal mechanism has left Scotland with England’s constitutional arrangement instead of her own? The argument, most notably put forward by Dicey, and so widely accepted that it is almost a required tenet of legal faith, runs as follows:

•The Union was not created by the Treaty but by the Acts of Parliament (Acts Union), which replaced the Treaty as the governing instruments of the Union;

•Of the two Parliaments which created it, one (the Scottish) ceased to exist at the Union and the other (the English) remained;

•(Implicit) There was no other seat of power in Scotland, the Scottish Privy Council having been abolished, and therefore the whole structure of Scottish government and of constitutional power was transferred to Westminster;

•Westminster, whose unbroken, English traditions continued unchanged, subsumed into itself the power of the Scottish Parliament so that Westminster may now alter the laws and government of Scotland as it wishes;

•Parliamentary Sovereignty passed from the English Parliament to the UK Parliament in Westminster and, (as this was the larger and only remaining Parliament), thereafter applied uniformly across both England and Scotland

We have already seen that this argument entirely ignores the status of the Claim of Right as a ratified condition of the Union. If there was no danger that this status might be misrepresented as being subject to Westminster’s sovereignty, (along with all the other articles of the Act of Union), we could ignore Dicey completely. Given the logical contortions which are already required by the Diceyan argument, however, that is notbeyond the bounds of possibility. And so it remains important to establish whether the Diceyan argument is solid or not.

It depends on whether or not the first two propositions are true. If they are true, (and if the ratification of the Claim of Right is just another Article of Union!), then it can be argued that Westminster extended the reach of its absolute sovereignty into Scotland in 1707 and is still entitled to do so. That would mean that any aspiration of the Scottish people to independence from the rest of the UK is simply the ambition of a component part of a whole, a component which is subject to the authority of the UK Parliament and dependent on that Parliament for permission to separate itself from the larger body.

If they are false, however, then so is Westminster’s right to behave as though Scotland’s constitutional provisions and safeguards had ceased to exist. And there is not merely a flaw in the Diceyan argument; there is error, omission and one absurdity so glaringly obvious that, once seen, it becomes as naked as Andersen’s Emperor.

Argument: The Union was created by the Acts of Two Parliaments which replaced the Treaty as the governing instruments of the Union

The history and texts of the Acts of Union record the roles of the Parliaments of England and Scotland, not as the creators of the Union, but as the ratifying bodies whose statutes, the Acts of Union, gave force to a treaty, The Treaty of Union:

•Both Parliaments agreed to the opening of negotiations for Union in 1705. Following this, thirty one Commissioners were appointed from each country. Royal Commissioners, reporting to the monarch and negotiating terms, represent the process of agreement to a treaty. It is a wholly distinct and separate route from that which is, or ever has been followed in the enactment of a Parliamentary Bill.

•The resulting agreement, the Treaty of Union, was ratified in 1706 (England) and 1707 (Scotland) by the incorporation of the Treaty Articles into Acts of the English and Scottish Parliaments known as the Acts of Union. Neither the Parliament of England or Scotland drafted the wording of what should, more accurately, be known as the Acts of Ratification. And no parliament requires to ‘ratify’ its own legislation:

(an) “Act ratifying and approving treaty of the two Kingdoms of Scotland and England. [January 16, 1707]

(Preamble) The Estates of Parliament, considering that Articles of Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England were agreed on 22nd of July, 1706 by the Commissioners nominated on behalf of this Kingdom, under Her Majesties Great Seal of Scotland bearing date the 27th of February last past, in pursuance of the fourth Act of the third Session of this Parliament and the Commissioners nominated on behalf of the Kingdom of England under Her Majesties Great Seal of England bearing date at Westminster the tenth day of April last past in pursuance of an Act of Parliament made in England the third year of Her Majesties Reign to treat of and concerning an Union of the said Kingdoms …

Article XXII That by virtue of this Treaty, Of the Peers of Scotland at the time of the Union 16 shall be the number to Sit and Vote in the House of Lords, and 45 the number of the Representatives of Scotland in the House of Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain; … Which Act is hereby Declared to be as valid as if it were a part of and ingrossed in this Treaty

•Neither Parliament pretended that the creation of the Union between two sovereign and independent nations was within its competence. Nor would such a claim have made sense to the negotiators, since agreements between sovereign nations can only be concluded by treaty. The treaty then stands above the domestic law of both nations so as to impose obligations and conditions jointly on the signatories, ensuring that neither can alter it unilaterally other than in specifically explicit and pre-agreed exceptions. (Such as those itemised in the Articles of Union.)

Thus the two parliaments ratified a contractual partnership between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland through a treaty which, in common with all treaties, conferred certain rights and imposed certain obligations on both parties. It came into force at ratification.

The English ratifying Act approved the Articles and the Scottish Act without further amendment, and enacted that “the said articles of union so as aforesaid ratified approved and confirmed by Act of Parliament of Scotland and by this present Act… are hereby enacted and ordained to be and continue in all times coming the complete and intire union of the two kingdoms of England and Scotland”. This did not however and could not make the English Act the sole constituent of the Union, as the parliament of England had no legislative power in relation to Scotland.

Ratification did not convert the Treaty into an Act or Acts, nor are there words in either Act which incorporated the Treaty or any part thereof into Scots or English domestic law, as is now sometimes done with international conventions. Ratification implies that the Treaty had been made already and expressed that it had been finally accepted and was beyond alteration.

But, at this point, according to the Diceyan argument, it also ceased to have force as the governing instrument of the Union and was replaced by the Acts of Union.

How did ratification replace the treaty as the governing instrument of the Union?

After ratification, the Scottish Parliament, at least, ceased to exist. According to Dicey, this meant that one parliament remained, the English Parliament, (with the addition of forty five Scottish MP’s and sixteen Scottish nobles). This left Westminster holding the Union in place, not by the force of the treaty it had ratified, but by its solitary, ratifying, English statute.

What, then, did the Acts ratify? What came into force at ratification? Can the Acts that unambiguously refer to the treaty and to ratification be said to ratify themselves? Even if it were true that only Scotland’s parliament was dissolved, and the English Parliament remained, how could any international treaty be upheld, imposing the conditions and obligations agreed by the signatories, through the statutory competence of one signatory?

This is not only unheard of in treaty law, it is an obvious absurdity.

What difference does the it make whether the Union is governed by a Treaty or by the English Act of Union?

The difference lies in the degree of freedom that Westminster does or does not have to alter the conditions of the Treaty at will.

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is not known for its observance of international treaties, nonetheless it has ratified the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) and thus has a commitment to recognise the particular and binding nature of Treaty Law:

From the perspective of international jurisprudence, the foundational prescription is pacta sunt servanda; treaties are to be respected and international obligations must be obeyed… Treaties and other forms of international law, therefore, occupy the apex of the legal pyramid and all domestic authorities of any particular country—whether denominated as rules of its national constitution, ordinary legislation, or in any other manner—are subsidiary. A country may not, under this system, interpose domestic law as a justification for its failure to meet treaty requirements. If it could, there would not be much point in concluding such agreements.

How convenient it would be for signatories to an international treaty to be able to argue that their ratifying legislation had replaced the Treaty itself and that, as statutory legislation falls under their own competence to alter, they are free to alter the conditions of the original treaty. But if this were lawful, it would negate the whole purpose and foundation of treaties in the first place. This is exactly Dicey’s argument, however, and despite the subversion of every principle of treaty law which it implies, it appears to be almost universally accepted.

In the specific context of the Treaty of Union, in which the standing and self-determination of an entire nation was soon to be determined by its numerically superior ‘partner’, the absurdity of the argument becomes even clearer.

We are asked to imagine that the negotiations for the Treaty of Union concluded with the clear understanding of the Scots contingent that, after ratification, the hard fought terms would be imposed and protected, not by the treaty itself, but by the acts passed by the two parliaments. Then we have to imagine it was also clearly understood that, as the Scottish parliament would cease to exist, all authority to alter or ignore the terms of the Treaty would pass to the new joint parliament in Westminster. And ever after, its terms and conditions must be defended from alteration if necessary, by the overwhelmingly outnumbered Scottish MP’s. (The Scots were allowed just one more MP than Cornwall.)

If it is unimaginable to the modern mind that such an application of the treaty agreement was contemplated by the commissioners, or the Scottish Parliament of 1707, it would surely be beyond belief to those who crafted or signed the treaty.

Within the context of treaty law in general and the context of the Treaty governing the Union specifically, the notion that Dicey’s first proposition is either sound, lawful practice or was ever imagined by the Commissioners for the Treaty or by the Scots Parliament is, without exaggeration, grotesque.

Conclusion: The first Diceyan proposition fails

Argument: Of the two Parliaments which created it, one (the Scottish) ceased to exist at the Union and the other (the English) remained

Notwithstanding its being located in the same building and resembling the old English Parliament in every physical characteristic, (apart from the number of new MP’s and Peers), the new Parliament of Great Britain was not the continuation of the English Parliament with the addition of some Scots.

The Treaty of Union extinguished both former Parliaments, created a new legal entity and, in principle at least, preserved the traditions of each even-handedly. And, like the question of whether the Union was created by Treaty or by Act of Parliament, the room for debate is negligible.

(Article XXII) And that if her Majesty, on or before the 1st day of May next, on which day the Union is to take place shall Declare under the Great Seal of England, That it is expedient, that the Lords of Parliament of England, and Commons of the present Parliament of England should be the Members of the respective Houses of the first Parliament of Great Britain for and on the part of England, then the said Lords of Parliament of England, and Commons of the present Parliament of England, shall be the members of the respective Houses of the first Parliament of Great Britain, for and on the part of England:

….. And the Lords of Parliament of England, and the 16 Peers of Scotland, such 16 Peers being Summoned and Returned in the manner agreed by this Treaty; and the Members of the House of Commons of the said Parliament of England and the 45 Members for Scotland, such 45 Members being Elected and Returned in the manner agreed in this Treaty shall assemble and meet respectively in their respective houses of the Parliament of Great Britain, at such time and place as shall be so appointed by Her Majesty, and shall be the Two houses of the first Parliament of Great Britain, And that Parliament may Continuefor such time only as the present Parliament of England might have Continued, if the Union of the Two Kingdoms had not been made, unless sooner Dissolved by Her Majesty;

Conclusion: As the present Parliament of England might have Continued? Thus the second Diceyan principle fails. If the Scottish Parliament extinguished itself, it is equally the case that the English Parliament did the same. Since neither original Parliament survived, which means that the English Parliament did not simply continue with the addition of a few Scots, there is no more reason to assume that the new parliament in Westminster inherited English Parliamentary sovereignty than that it inherited the Scottish popular sovereignty.

The remaining propositions

When the new Parliament of Great Britain was convened, it subsumed into itself all the powers and privileges of the two former parliaments of England and Scotland.

The powers of the parliament of Scotland, however, were not equivalent to those of England.

The Scottish Parliament did not possess or aspire to the authority of the English parliament. (And nor did the monarch in Scotland.) There was another, independent seat of power in Scotland, the nation itself and that power could not be transferred to Westminster. But whether because the English view of the Scots was that their monarchs were despots or because it was inconceivable, in a state based on Norman feudalism, that monarch and parliament could be held accountable by their inferiors, the reality of popular sovereignty was entirely overlooked.

It does not appear to have occurred to any jurist or commentator, up to and including Dicey, that the source of authority in Scotland had not been transferred to London along with the Crown and the Parliament. From the English viewpoint, with the Scottish Privy Council abolished, what was left in Scotland but a subservient population?

What was left in reality was the real seat of government authority in Scotland, the people. And what remained was the right of that power of Scotland, the people, to exercise their sovereignty through their own assemblies, councils and conventions, including the assembly of all the communities, the Convention of the Estates. And since the nation of Scotland was never subsumed into the nation of England and the people of Scotland did not become members of the English nation, the power vested in the people has always remained vested in the people, never subsumed into the grasp of Westminster.

It is a pity that Scotland’s parliamentary records were consigned to oblivion for so long. It is a pity that mistaken assumption and prejudice have so long directed real insight into Scottish political and constitutional history. But errors do not become truths because they have been accepted and taught. And what did not fall under Westminster’s reach, because it had never fallen under the reach of either king or parliament, remains out of Westminster’s reach and beyond the reach of English parliamentary sovereignty today.

Unless, of course, the error is allowed to stand unchallenged and an authority that never belonged to Scotland’s parliament is allowed to pass to Westminster!

Conclusion: It is time for A. V. Dicey to be removed from the interpretation both of Scotland’s constitution and of her rights under the provisions of the Treaty of Union

BEAT THE CENSORS

Sadly some sites had given up on being pro Indy sites and have decided to become merely pro SNP sites where any criticism of the Party Leader or opposition to the latest policy extremes, results in censorship being applied. This, in the rather over optimistic belief that this will suppress public discussion on such topics. My regular readers have expertly worked out that by regularly sharing articles on this site defeats that censorship and makes it all rather pointless. I really do appreciate such support and free speech in Scotland is remaining unaffected by their juvenile censorship. Indeed it is has become a symptom of weakness and guilt. Quite encouraging really.

FREE SUBSCRIPTIONS

Are available easily by clicking on the links in the Home and Blog sections of this website. by doing so you will be joining thousands of other readers who enjoy being notified by email when new articles are published. You will be most welcome.

What's Your Reaction?