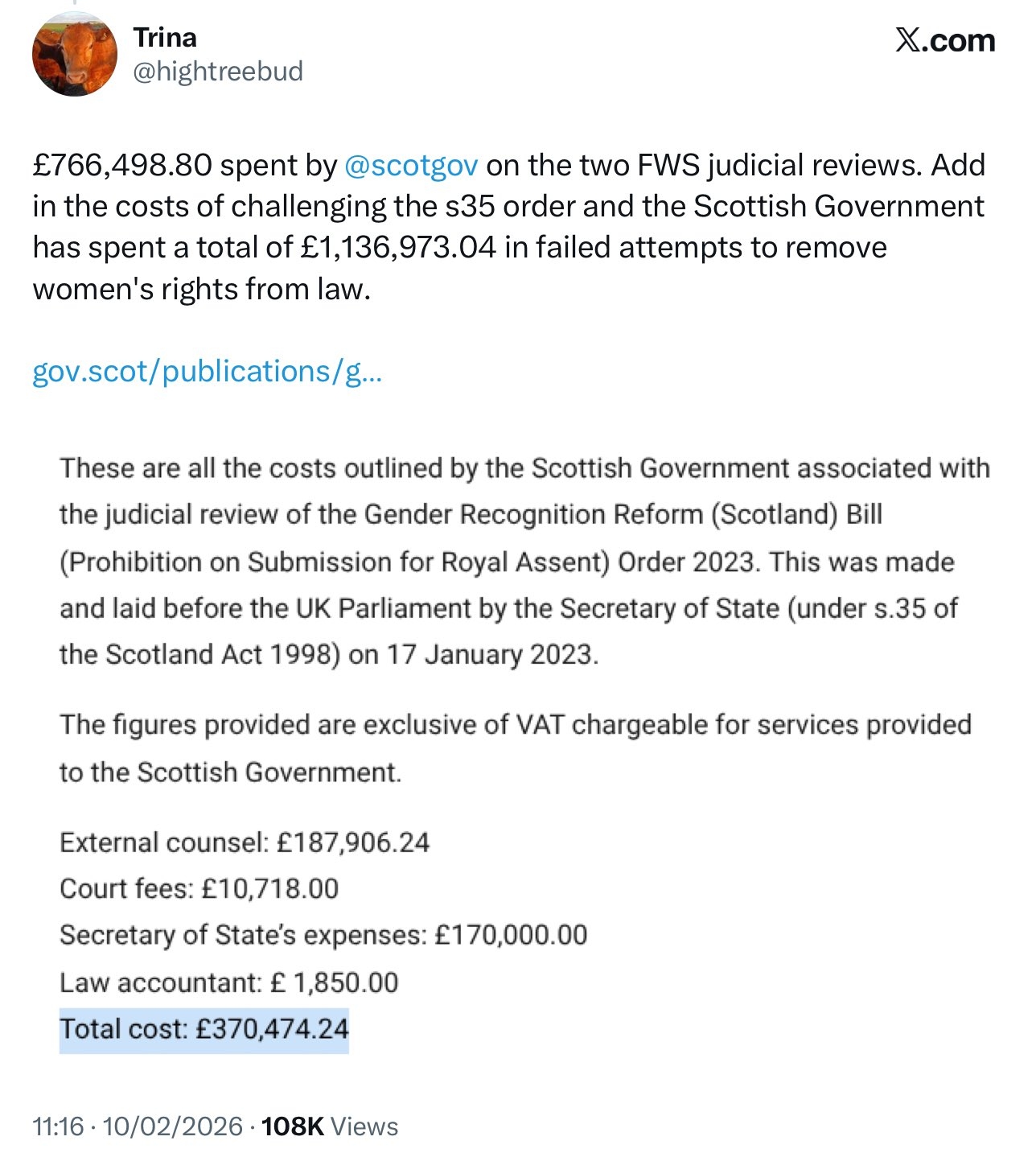

Independence Will Not Happen Automatically

Despite opinion polls more favourable to Independence and regular contributions from Scotland’s liberal elite that “the Union in retreat is a banal fact of Scottish life”, independence for the people of Scotland will not happen overnight or automatically. To promote and assist this, two things above all need to happen:

- Scotland needs a popular and well publicised, credible set of economic and social policies for its own people – which it has never had since 1997.

- Members of the Scottish National Party need to gain control of the Scottish National Party. In an age when social democratic parties throughout Europe have collapsed into their central bureaucracies, with many struggling to achieve more than 10% at the ballot box, the SNP exists today as an almost historical example of what used to be labelled “democratic centralism”, with most decisions taken by a handful of key people. Their specified aversion to any semblance of an Independence Plan B means that Scotland may not enjoy the luxury of real debate on alternative ways forward.

With Tom Devine’s astute observation that Brexit has probably made a “deep and possibly even decisive impact”, we now have a golden opportunity to be propelled faster to Independence as Johnson’s agreement with the EU rapidly degenerates into a mass of small print and contradictions, for which Scotland’s political establishment has done little to prepare.

May I deal with the SNP first, since current Party developments for some of us bring back brilliantly clear memories of debates in the Labour Party during the 1970s and 1980s, which mainstream media constantly labelled ‘arcane constitutionalism’? For many of us then it was vital that the Party gained control over policies and Election Manifestoes. Despite changes during its recent NEC election, the SNP as a Party still needs to move to a situation where:

- Constituency Parties freely elect their own convenors and officers

- Constituency Parties freely chose their own Parliamentary and Council candidates

- Annual Conferences and the National Executive Committee determine policy

- SNP Election Manifestos, based on Conference policies, are unambiguously published by the NEC on behalf of the Party rather than ventriloquised by Scottish Government and Charlotte Street Partners.

In 1990 the Labour Party emerged from a Labour Representation Committee which included socialist associations and trade unions. As a result, the Party retains these close relationships, so that many of us still have important voting rights through our unions and the Cooperative Party. Despite becoming a mass membership Party in 2014, the SNP has never experienced any similar process of democratisation. In particular, all those throughout Scotland who displayed their homemade posters in fields and bedroom windows have never been accommodated within what should be the wider movement of the SNP. Instead, they desperately seek shelter with All Under One Banner, Independence Regional List parties, Common Wheel Groups and Independence Hubs like Yes Inverclyde. Independence is more than a political party. It should be a movement.

When for family reasons I arrived in Scotland in 2004, policy perspectives on the surface looked progressive. Scotland still had Social Justice Officers, Social Inclusion Partnerships (SIPs), Communities Scotland and “Closing the Opportunity Gap”. But I soon discovered that this was hardly matched by progress at ground level.

After nearly 15 years of Conservative Government, in December 1997, as new Scottish Secretary, Donald Dewar asked senior civil servants to develop a “corporate approach to promoting social inclusion within Government”. But when in 1999 “Social Inclusion: Opening the Door to a Better Scotland” appeared, he had already written that Glasgow’s regeneration strategy “should be based on the assumption that no additional public resources can be provided”. So by 2005, the Scottish Executive’s “Social Focus on Deprived Areas” was reporting that “Nearly one in three (30%) young people aged 16-24 in Scotland’s 15% most deprived areas are not in education, employment or training, compared with to 13% in the rest of Scotland”. By 2007 Ivan Turok at the University of Glasgow in “Urban Policy in Scotland” was writing about a New Conventional Wisdom – a “set of shared ideas and assumptions that depart from the old consensus”. He continued that “Many manifestations of the new thinking, particularly in the United States, have a relatively narrow conception in that they pay little or no attention to issues of social inclusion and cohesion. Social conditions are only relevant to city prosperity when they become so bad as to undermine competitive success through crime, disorder and negative attitudes to work and education”.

So, despite surface appearances, the import of policies from England had continued. Though a Blair New Labour Government had signed the EU’s Treaty of Amsterdam in October 1997 and accepted the Social Chapter, from which at Maastricht in 1992 John Major had opted out, Blair’s preference for market solutions meant that Scotland’s hopes of joining other EU nations to press for more emphasis on social policy had already been dashed. The Scottish Executive’s 2001 “Smart Successful Scotland”, with its emphasis on entrepreneurs and business startups, was soon followed in June 2002 by “Better Communities in Scotland: Closing the Gap”. Social Inclusion Partnerships were soon absorbed into Community Planning Partnerships by the 2003 Local Government in Scotland Act, with a duty to produce Regeneration Outcome Agreements, with ‘best practice’ outcomes determined centrally rather than by local communities. Scotland’s “pathfinder” Urban Regeneration Companies in 2003 for Craigmillar, Raploch in Stirling, and Clydebank Rebuilt followed those in England. Chik Williams’s “Story of the Clydebank Independent Resource Centre” describes their policies of land assembly to improve private investment opportunities. In May 2004, the Royal Bank of Scotland’s “Wealth Creation in Scotland” – with its preface by Jim Wallace MSP, Minister for Enterprise and Deputy First Minister - extolled the virtues of Stagecoach and globally focussed companies. The role of public investment was to boost private sector competitiveness. So when we crowded into Glasgow University’s Adam Smith Building in March 2006 for the launch of the “People and Place” regeneration policy, we were not surprised to hear from the Head of Scottish Executive’s Regeneration Division that Scotland was open for business. He continued that Ministers “felt the need to say something about regeneration.” Many of us could see that any hope of policies different from England had disappeared.

Though a new Scottish Government in 2007 formed a Community Voices Network, “community engagement” was soon delegated to Paul Zealey Associates, a private firm. In reality the Network’s role was to fashion policies for incoming private firms to feel safer investing in “community enclaves”.

More recent manifestations of Scotland’s capitulation to London policies can be seen in the Report of the Christie “Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services” in June 2011. Many of its themes were a repeat from John Smith’s Commission on Social Justice in 1994, as an advance party for New Labour’s policies of workfare alongside Clinton’s 1996 “end of welfare as we know it” Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. Christie wrote that “Models of provision fail to empower and enable people and communities sufficiently to achieve positive outcomes in their own lives. Services often impair individual incentives and foster dependencies that create demand”.

Then came the Report of the Sustainable Growth Commission in May 2018. Rather than my own words, may I quote from Richard Murphy of Tax Justice, in what was hardly a Marxist analysis?

“In other words, the Scottish economy will, after independence, be run to keep the London money markets happy.

“The Scottish Growth Commission has proved to be a fantastic policy agent for the financial elite. But for those who hoped for a bright independent future it offers nothing but despair”.

This timid acquiescence was once more echoed in the Benny Higgins’ Advisory Group’s “Towards a Robust, Resilient, Wellbeing Economy” Report in June 2020, which reeled of recipes for the problems of Merseyside in the 1980s and the West Midlands in the 2000s. Among its more bizarre recommendations were copying the Government of Singapore with an “Emerging Stronger Task Force” and exploring a Universal Basic Income pilot with the agreement of the UK Government. Readers can decide which is worse - imports from Singapore or asking London first.

In anticipation of its release from any mainland European consensus, Johnson and London have already proposed Freeports and Enterprise Zones, with no taxes or regulations, are consulting on new procurement regulations for public services to be delivered by all comers, whether public or private and are discussing a down market shipping register to rival Panama and Liberia.

Space does not here permit the advocacy of a more comprehensive range of policies. Apart from a National Care Service, there should be targeted infrastructure spending and a host of reforms from Common Weal and other reports.

We need to give hope for a brighter future to the thousands in Scotland who daily risk their lives in care homes and hospitals to keep us alive, who queue for their late running privatised buses and trains home every night, and to the many university students, who though they do not pay tuition fees still have to work to pay living costs. They all need to feel more connected to a policy making process rather than struggling to survive under a Scottish policy making elite of around 200 people, who seem only accountable to themselves.

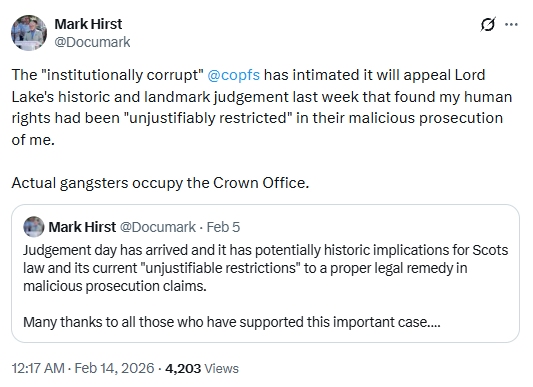

What's Your Reaction?